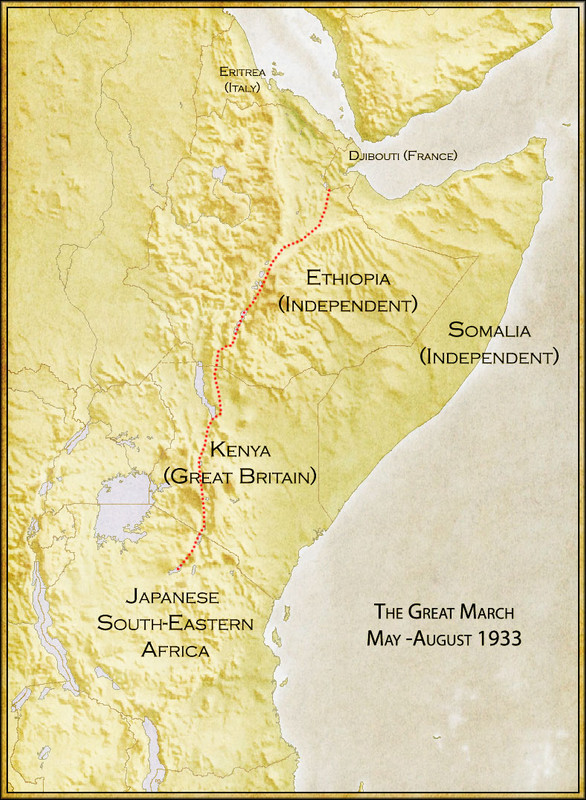

In February 1933, with the Japanese and French forces locked in a deadly stalemate in Djibouti, the Army Command sought out ways to upset the situation to the advantage of the Japanese. Feeding more troops to the entrenched French was deemed unacceptable, as any gains would not justify the cost in lives; instead, a daring scheme was proposed, in combination with the Foreign Office.

The Japanese had nearly fourty thousand native Askari troops in South-Eastern Africa, supported by the 1st African Artillery Brigade. If these forces could, somehow, be moved overland to Djibouti, they could open up a new front and, hopefully, overwhelm the French defenders. Unfortunately, there was a small problem: this would mean moving the equivalent of an entire army through British-held Kenya and, after that, the independent state of Ethiopia.

Ethiopia would not be a problem. Her Emperor, Haile Selassie, had often declared his hostility toward the French and Italian colonies to the north of his country; he was willing to allow the Japanese passage and even contemplated a formal alliance, provided the Japanese provide military aid and modern artillery to Ethiopia in return. Convincing the Brits to let the Askaris through Kenya would be a more tricky proposal - as it would be tantamount to Britain declaring war on France.

Secret negotiations began on the 20th of February, with Japan probing for a potential alliance. The British were more than hesitant at first, but a military analysis of the situation convinced His Majesty's Government that the French defense of Djibouti would be untenable in the long term and that providing assistance to the Japanese could serve as a major bargaining chip in the future. Yet, in classic British fashion, Albion decided to play both sides.

France had also been pushing the British for permission to open the Suez canal to her warships. So far, it had been the position of the British that the Canal would be closed to all combatants. Yet now, with the Japanese also pushing for permission to cross British territory, this situation changed.

On the 14th of March, the British declared that they would allow (under very specific and strict terms and conditions) the passage of military vessels, supplies, armament and personnel through 'canals and waterways' of His Majesty's African holdings. This permitted the French convoys to cross the Suez; but (less obviously) it also allowed the Japanese to cross Kenyan territory, provided they kept to waterways and canals (and the British authorities were more than willing to turn a blind eye in the few cases where that was impossible).

The march was gruelling and not helped by the fact that the rainy season (with soaring temperatures and pouring rain) was in full effect, but the Alliance Askaris handled the 2500+ kilometre trip with inhuman endurance. The Long March took them two full months, under the worse conditions imaginable; but their arrival in Djibouti, on the 30th of July, achieved their goal of complete surprise and smashed the Djibouti stalemate.

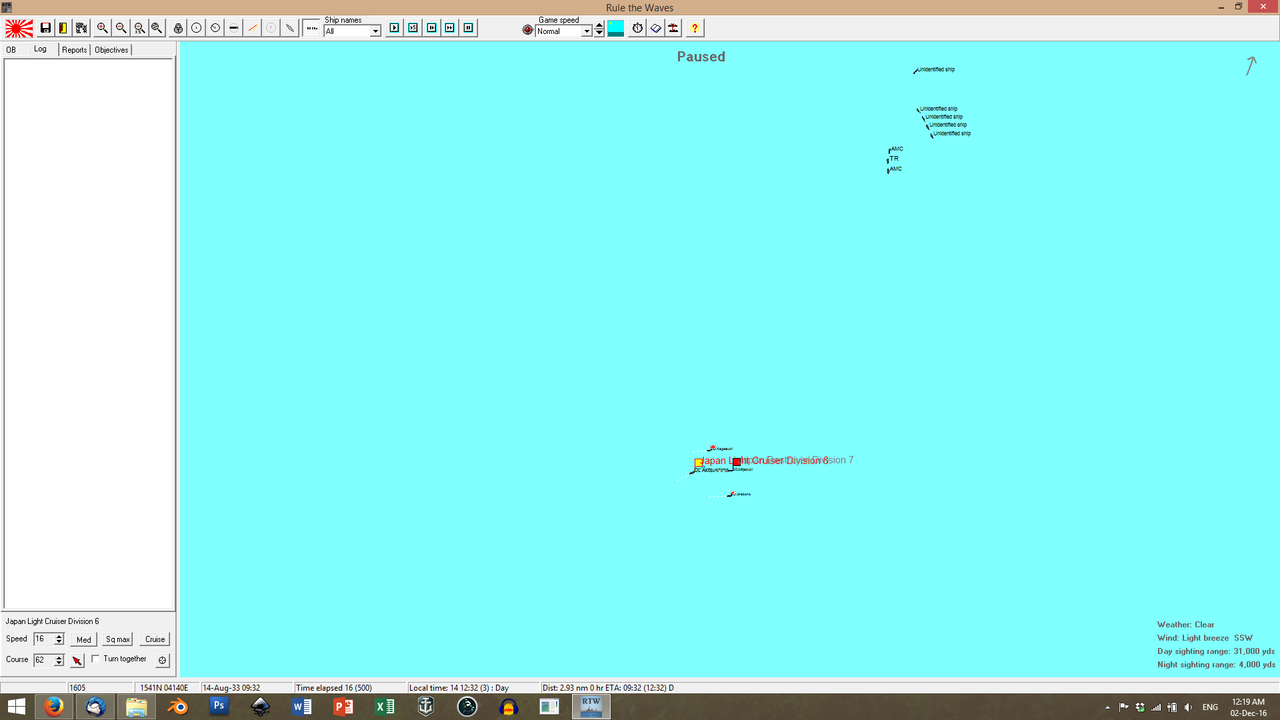

But not all news were good. France had delayed deploying her capital ships so far, but, with the Suez opened to her, that was no longer the case. On the 14th of August, the

Akitsushima, on patrol off the coast of Djibouti, received a message from I-75 that another major French convoy was en route.

Hiei was still en route back from Madagascar and at least two days away; Captain Uchida of the

Akitsushima decided to engage the French convoy with only his destroyer escort. The decision would prove disastrous.

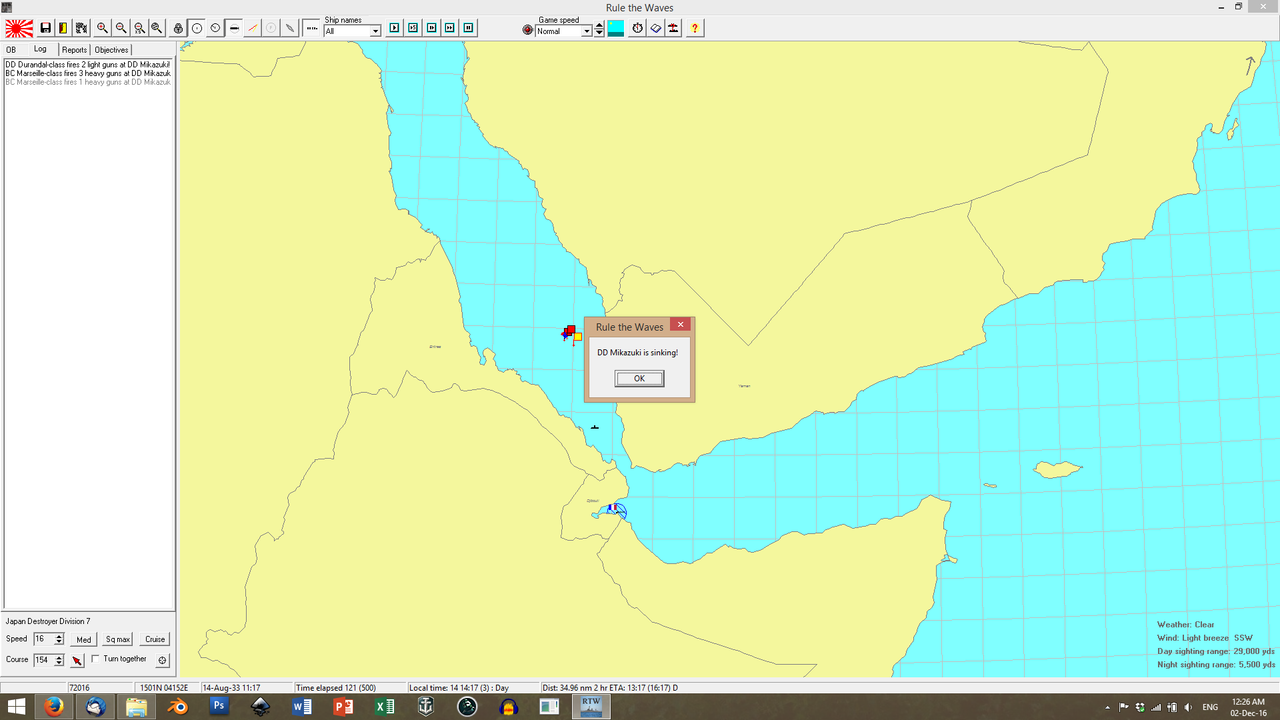

At 12:30, the

Akitsushima spotted the enemy convoy and moved to intercept. Long-range fire, scored multiple hits on a transport ship; the Japanese force closed in.

It is at this point that, out of the haze to the north and the ground clutter to the south, two more contacts appeared on the

Akitsushima's plot - both closing in at high speed. A few minutes before 14:00 hours, they had been both identified.

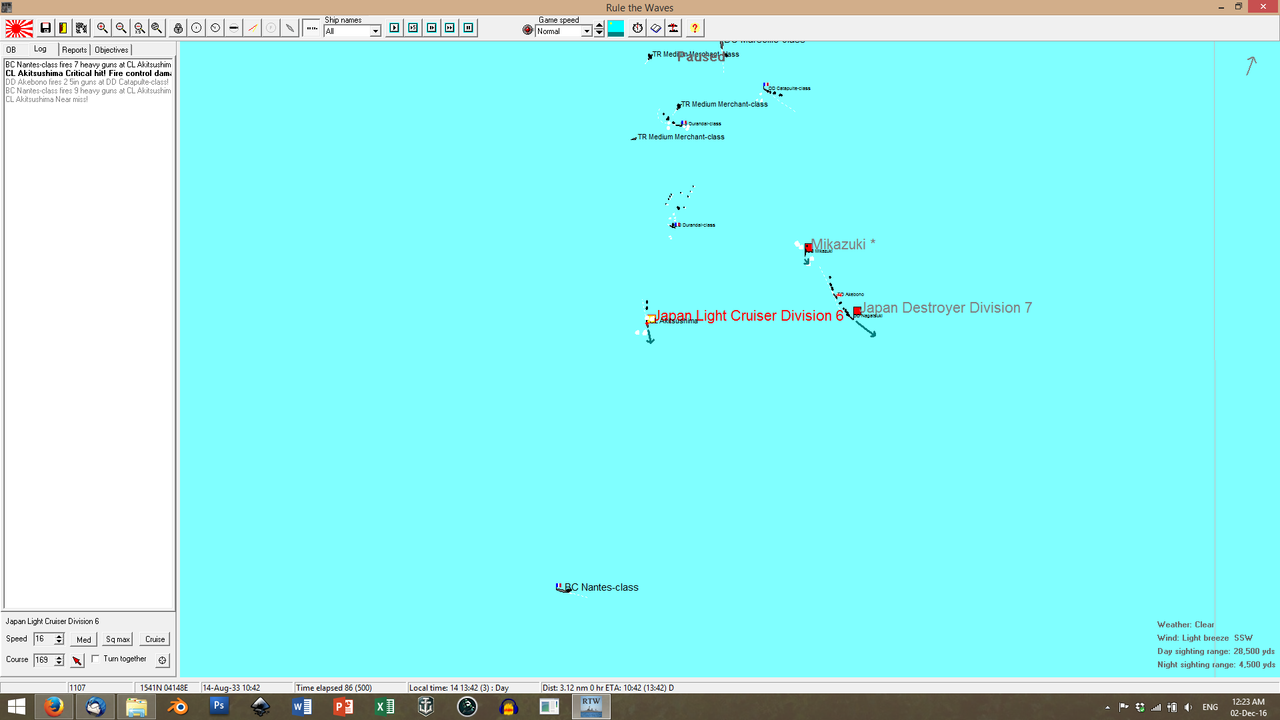

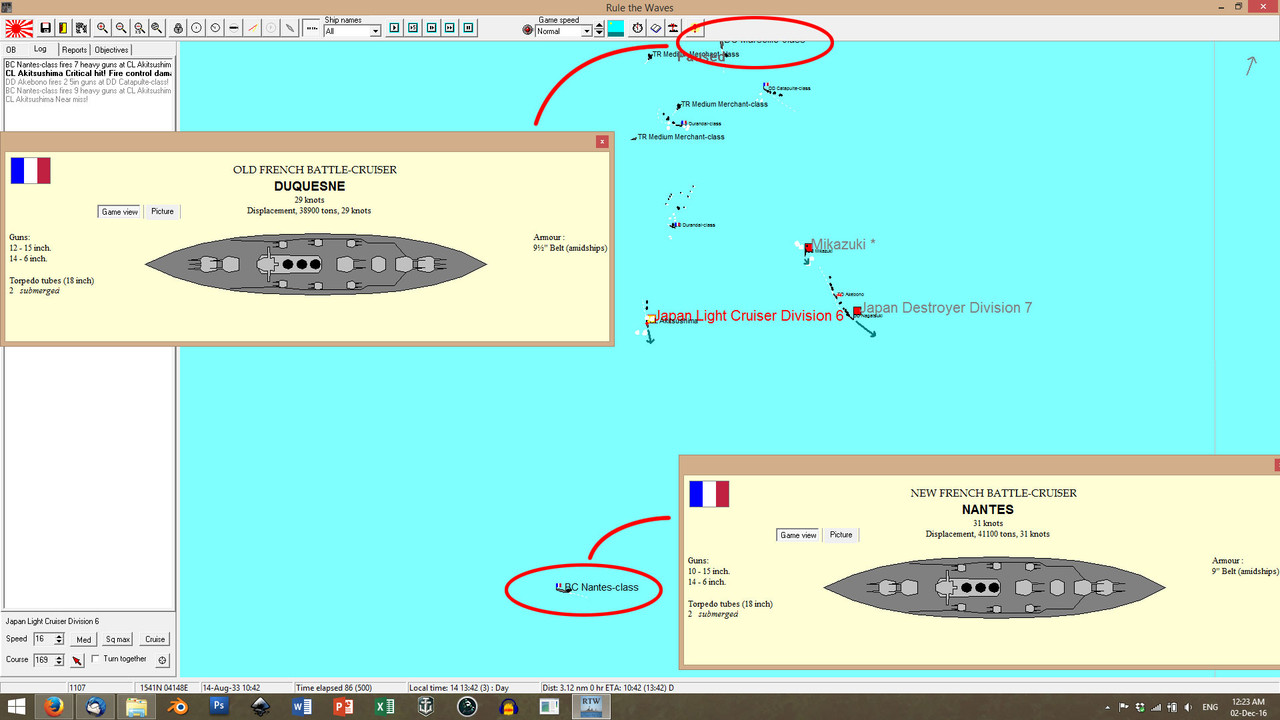

To the north, a

Marseille-class battlecruiser opened fire against the Japanese raider. And from the south, closing the jaws of the trap, a

Nantes-class battlecruiser approached, steaming at flank.

What happened from that point on is uncertain, but a few facts are known. Upon identifying the enemy capital ships, it became clear to Captain Uchida that victory or escape was impossible - at her best, the

Akitsushima could only do 29 knots and she had not been properly serviced in a while. He signalled his escorting destroyers to disengange and turned to close the range on the

Nantes, hoping for a torpedo attack.

Unfortunately, only the

Akebono managed her escape, as the French ships' gunnery focused on the destroyers. The

Mikazuki was hit on her torpedo launchers and the resulting explosion sheared the entirety of her superstructure away; the Nagatsuki came under concentrated fire from the battlecruisers' secondaries and slowly succumbed to flooding. It still savaged a French destroyer that closed in to finish the job.

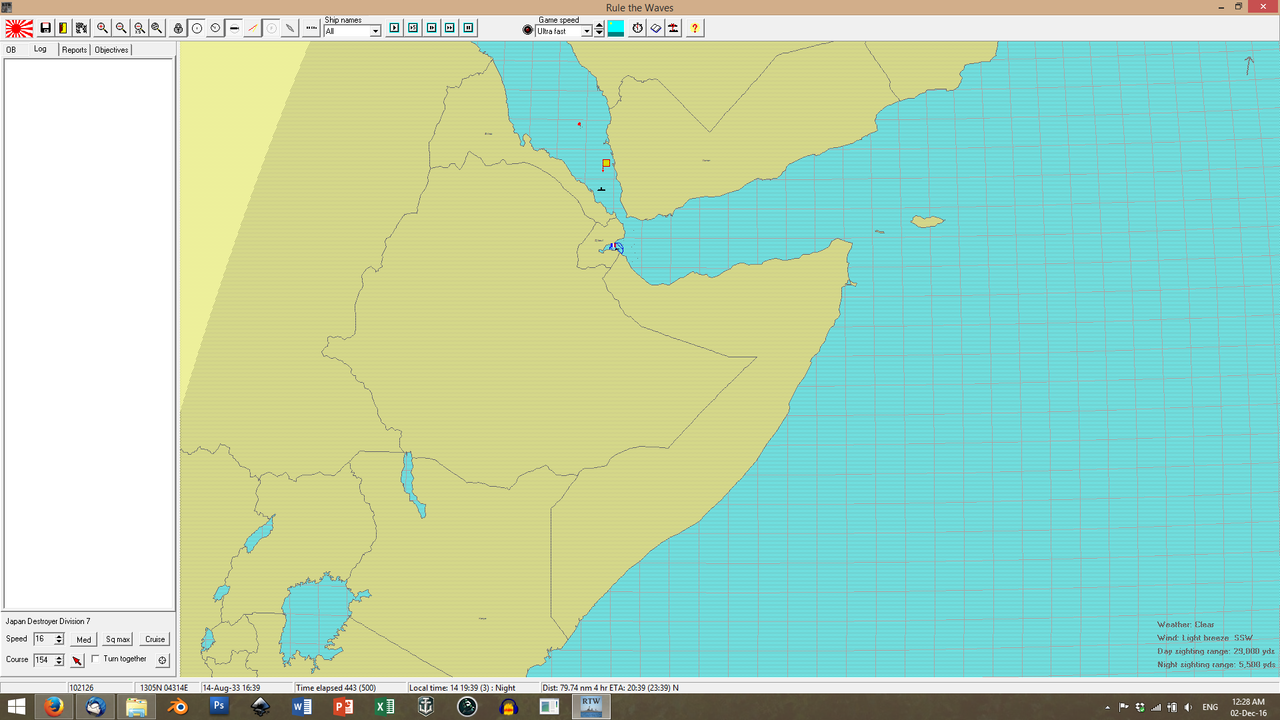

As

Akebono slipped under the horizon, she could see the enemy battlecruisers charging back to finish off the foundering

Akitsushima. The light cruiser's wireless set had long since fallen quiet and she was burning from stem to stern, but her main batteries were still firing.

At 18:35, the horizon behind the

Akebono erupted in a massive fireball; the thunder of the explosion reached the fleeing destroyer moments after. A 15-inch shell from the

Nantes had penetrated the forward magazines of the

Akitsushima. The French reported no survivors.

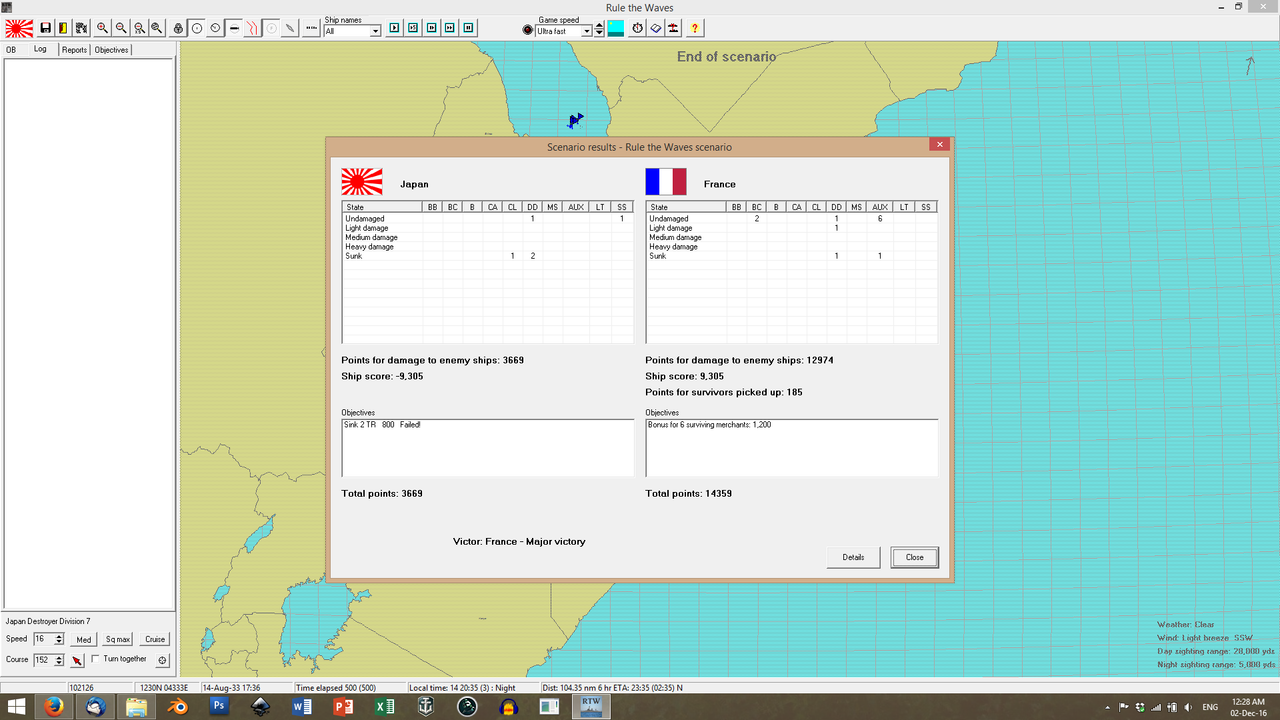

The deal with the British had allowed the Army to reach Djibouti; but had cost the Navy a precious light cruiser and two destroyers, for minimal returns. It was a

disaster.

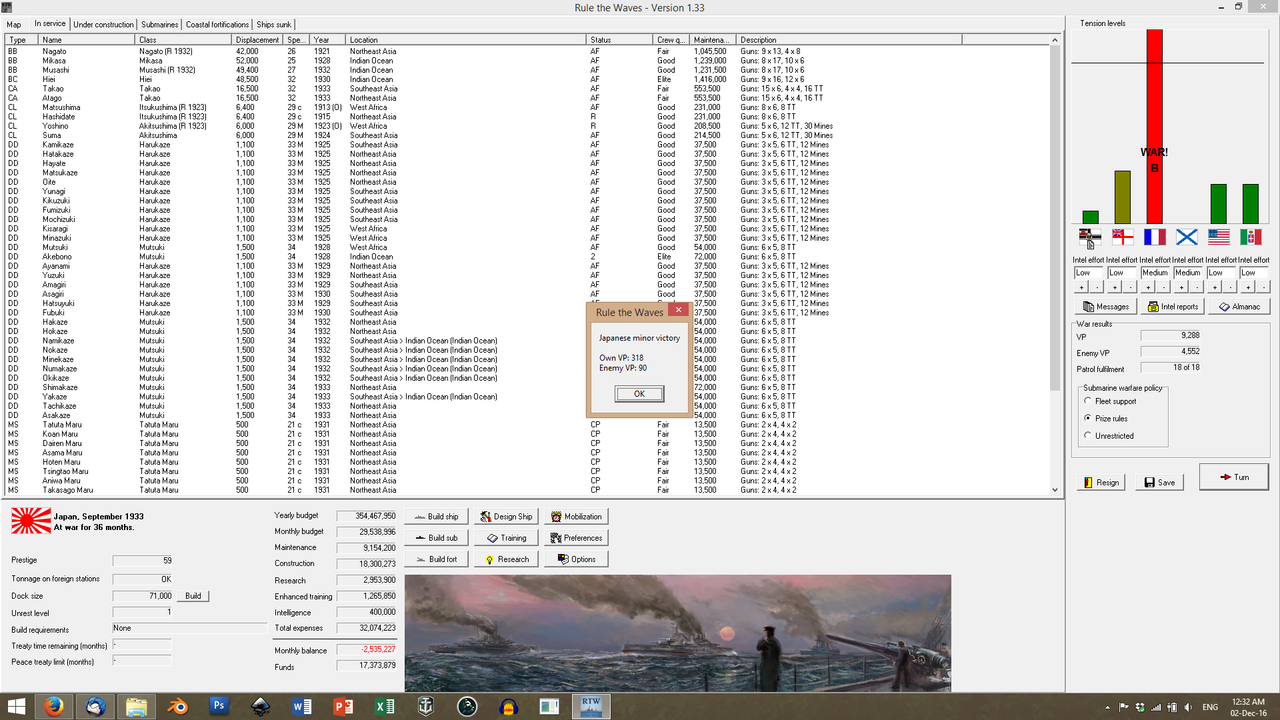

Unfortunately for the French, they could not afford to leave their battlecruisers in the Red Sea. With the sinking of the

Wittelsbach, the French fleet was

just big enough to reliably evade the German blockading ships, but not with two of their best battlecruisers absent from the Atlantic. As the Germans pulled the noose tight in September, the privations of war began to choke the French population; the

Nantes and

Marseille were recalled, having suceeded in resupplying the beleaguered defenders of Djibouti.

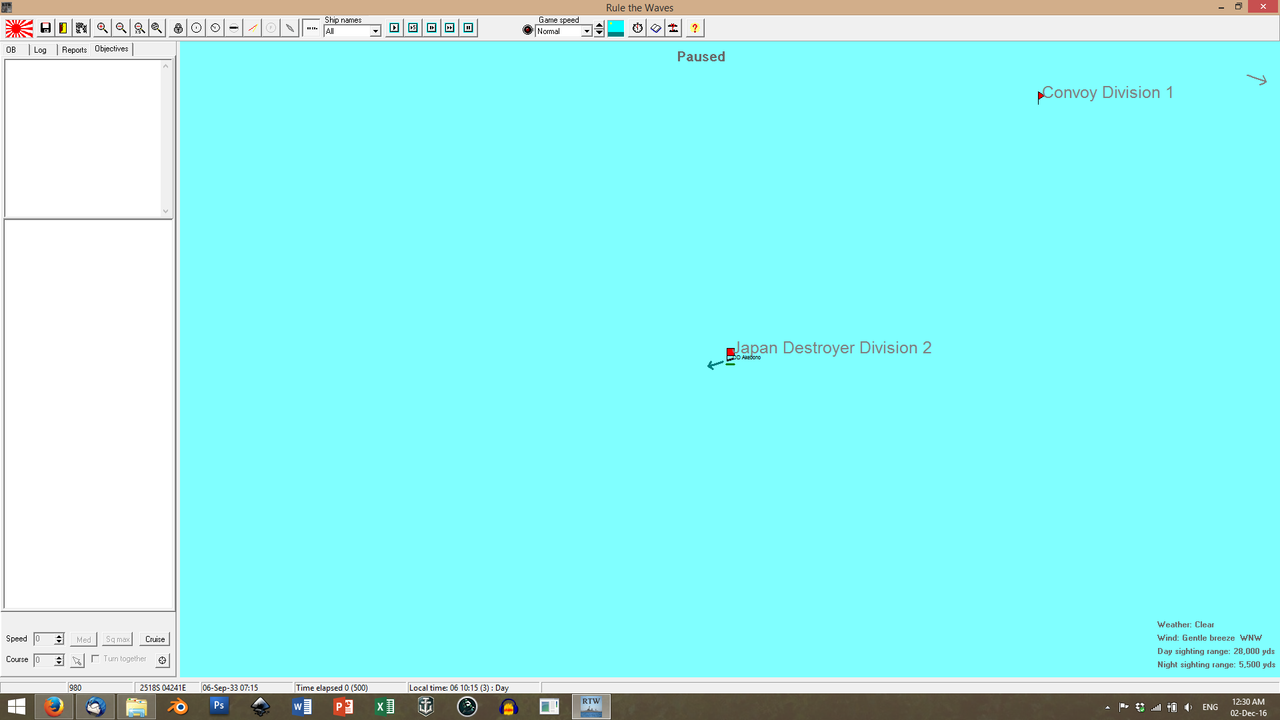

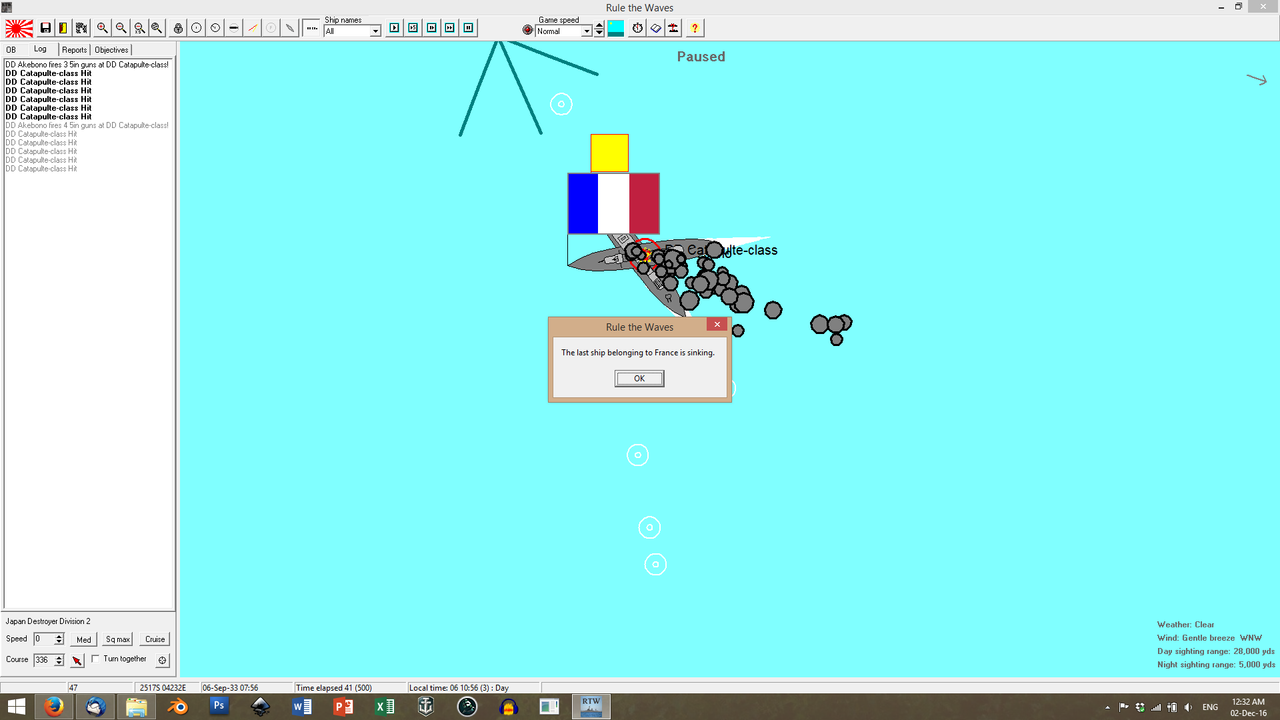

On the 6th of September,

Akebono returned to the coast of Djibouti, to patrol and confirm the departure of the French BCs. Upon her return, she was spotted and engaged by a French

Catapulte-class destroyer, the

Belier.

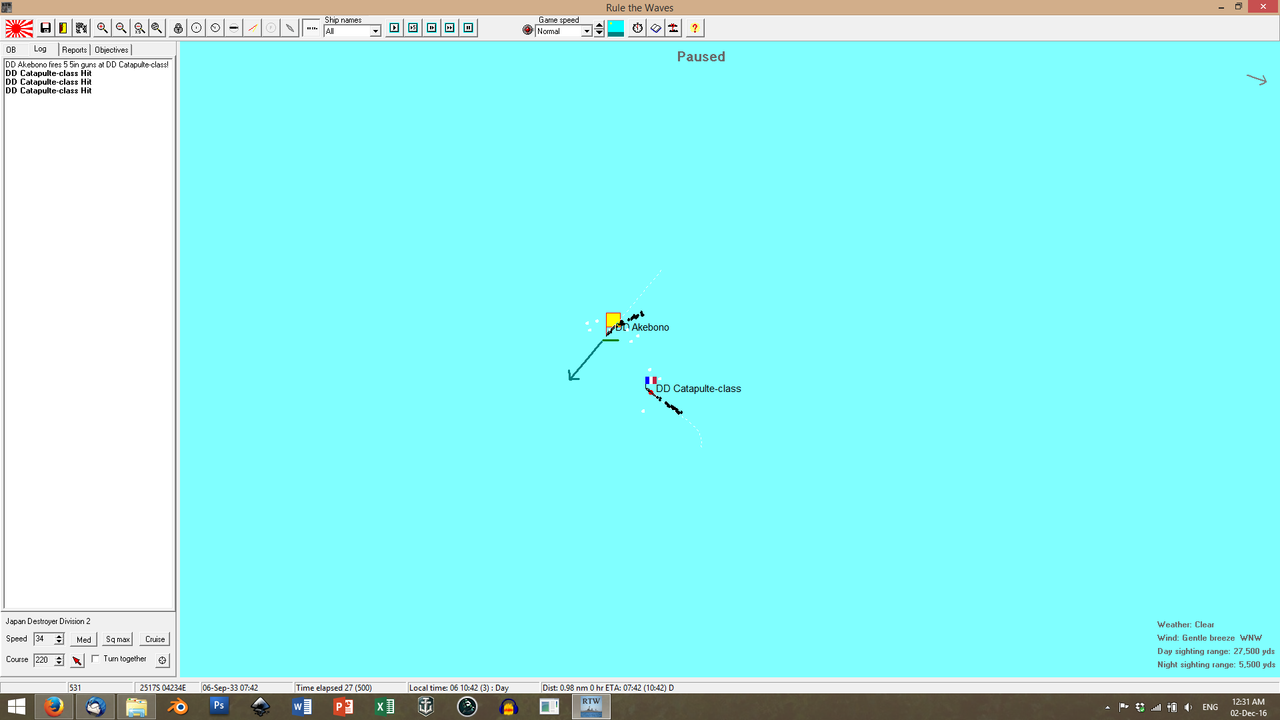

Commander Beauclerc of the

Belier immediately knew that his ship would not be able to escape the much more modern and well-armed Japanese destroyer. He ordered a frantic attack, to close the range and engage with torpedoes.

Unfortunately for him,

Akebono did not flinch. Captain Usawa brought his own ship around on a closing course and launched at point-plank range. In a mad turn to avoid the

Akebono's torpedoes, the

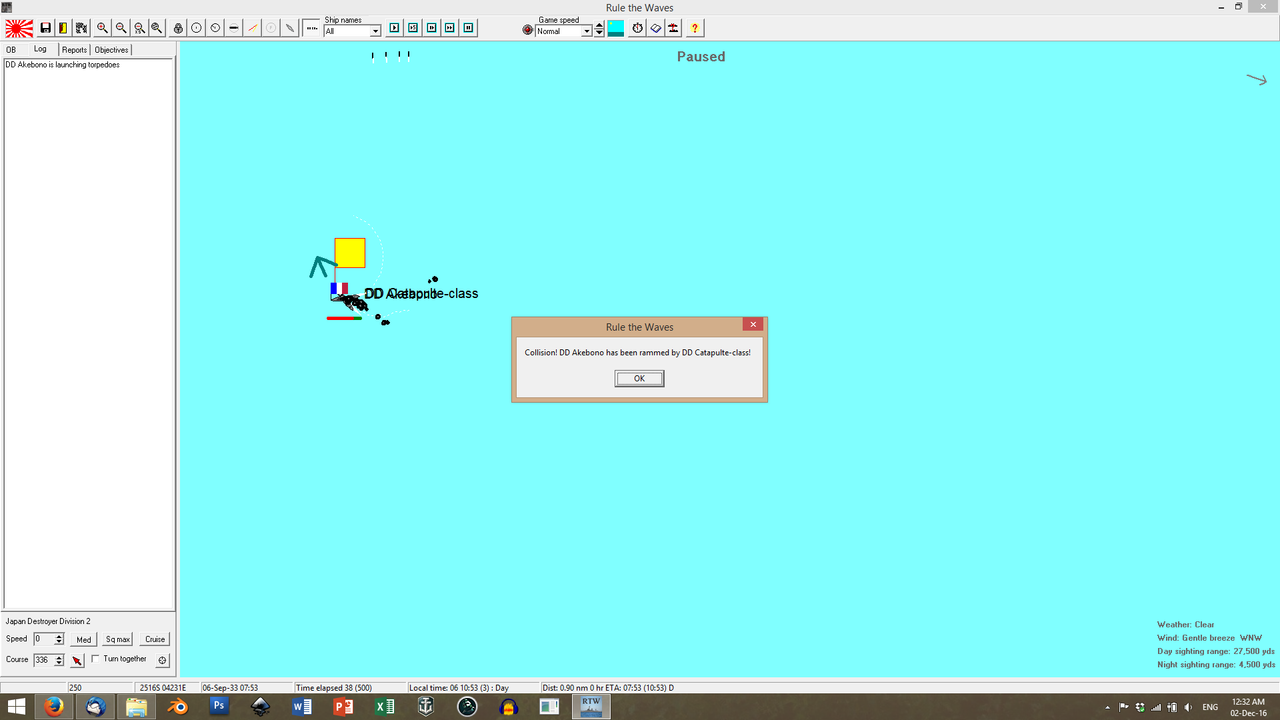

Belier rammed the Japanese ship.

The French ship's bow knifed into the

Akebono's own forecastle. Fortunately for the Japanese, the

Mutsuki-class destroyers had heavily reinforced bows, to support the weight of the two front-mounted turrets; the

Catapultes, with their deck-mounted guns did not have such an advantage. The bow of the

Belier crumpled like a concertina, locking the ships together; but the

Akebono suffered no heavy damage and her bulkheads stopped the flooding.

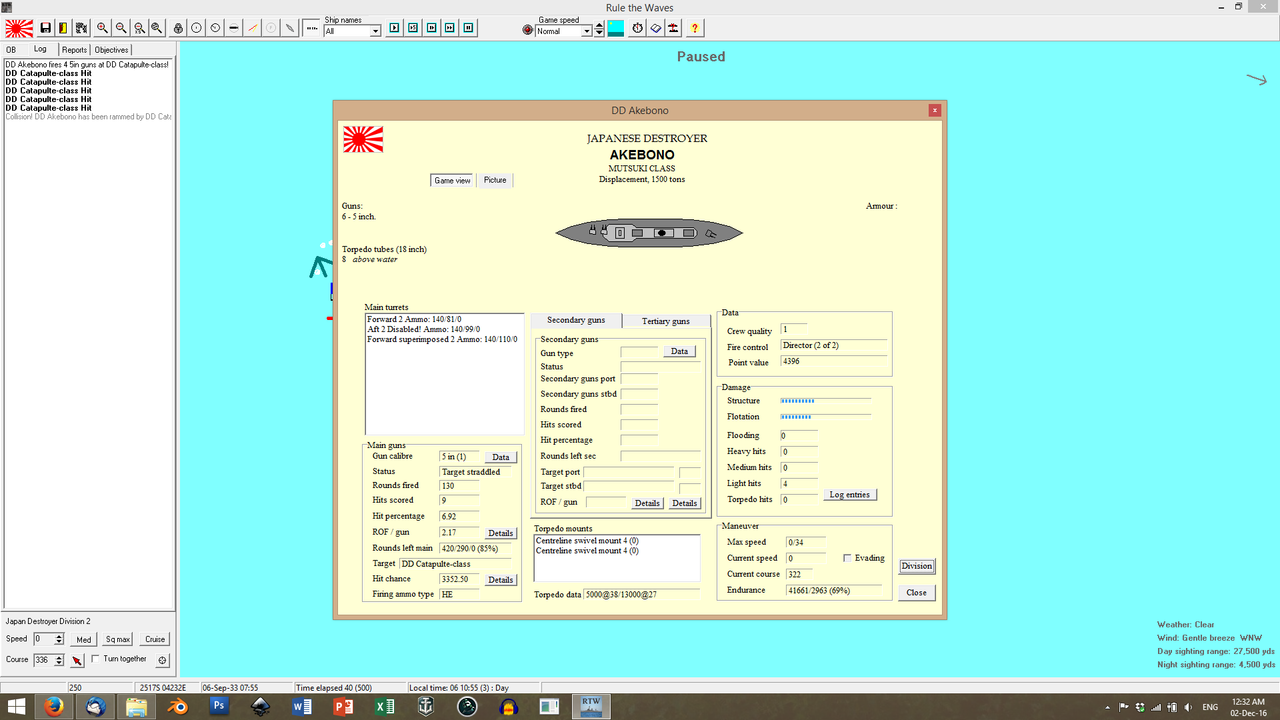

With her front guns smashed to bits and her boiler cracked, the

Belier hung on the

Akebono's side like a dead whale. Beauclerc ordered his men to strike the colours, but there was no time to execute the command. The loss of the

Akitsushima was still much too recent and the gunners of the

Akebono were itching for payback. Her rear turret had jammed under the shock of the collision, but her two front turrets were still functional and they opened fire at the

Belier's hulk at point-blank range. In the space of a minute, six shells smashed into the

Belier, punching deep into her broken vitals, sending shrapnel scything through superstructure and bodies, smashing her boilers and spilling flaming fuel all over her decks and internal compartments. By the time Usawa ordered a cease fire, only three men of the

Belier's crew of 160 were still alive.

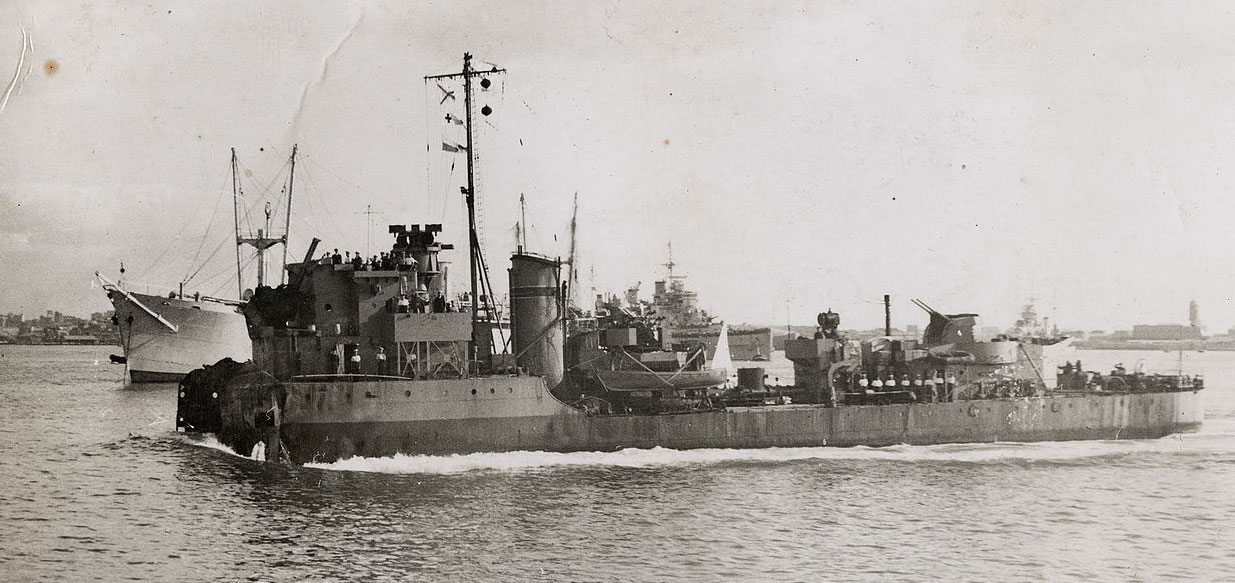

As the Japanese sailors attempted to disentangle their ship from the wreck of the

Belier, it became obvious that the structural integrity of the

Akebono would be compromised during the long trip back to Madagascar. Usawa ordered his men to take up axes and power-saws.

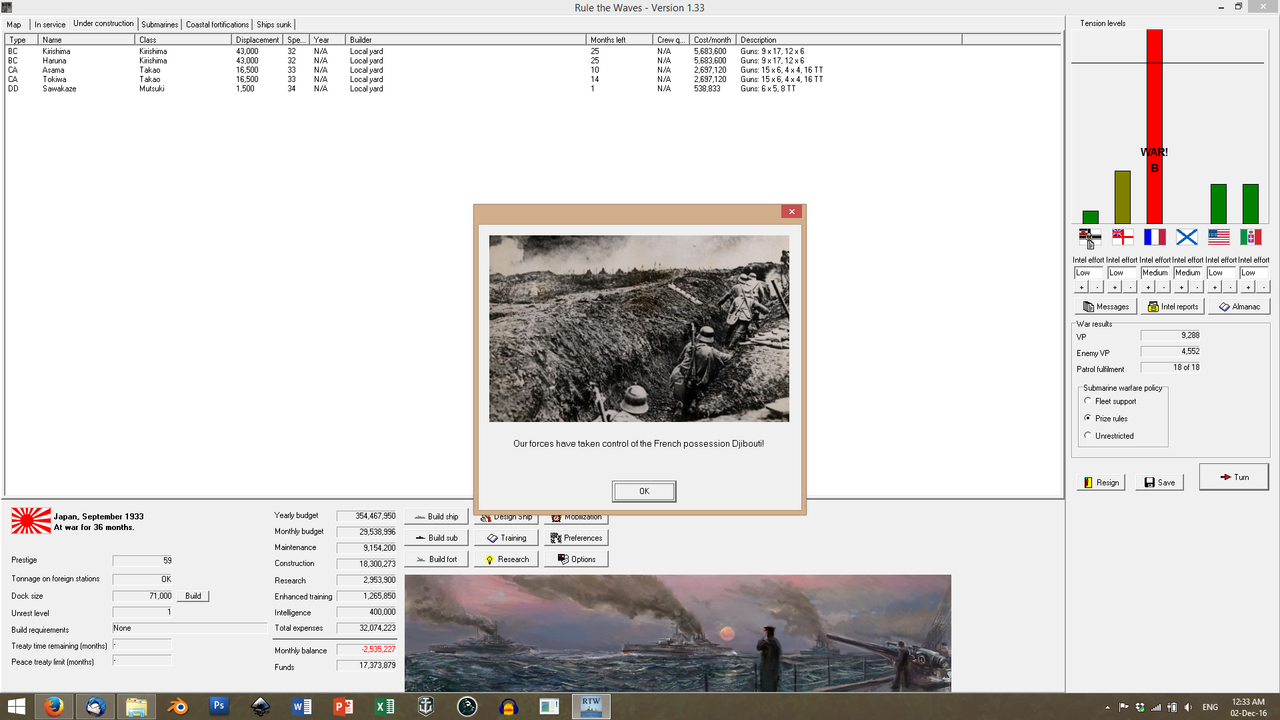

Four days later, the

Akebono reached Madagascar, her crew having removed the entirety of the ship's bow and relying solely on internal bulkheads. They were hailed as heroes for their amazing seamansship.

And only two days after

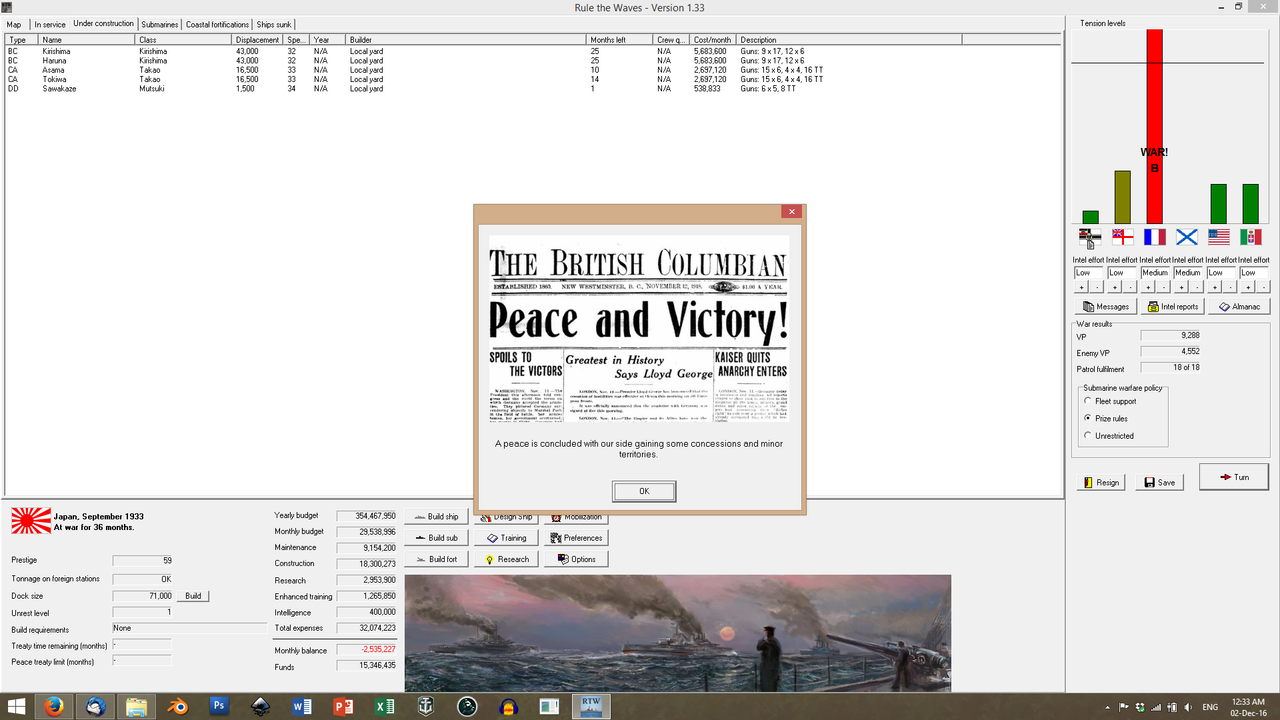

that, the last defenders of Djibouti capitulated. The Admiralty rejoiced.

Now it would be possible to sail the battle fleet north, through the Suez and into the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, to completely and

utterly lockdown the French blockade. Total victory was in sight.

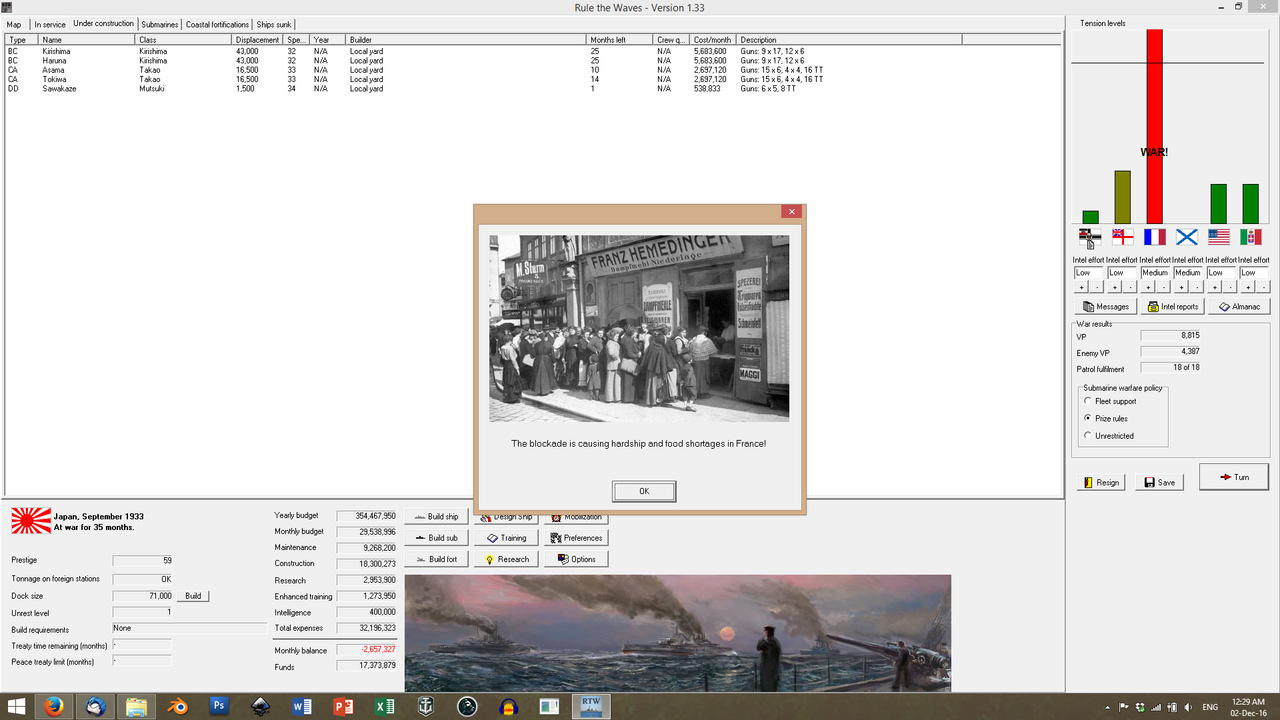

And in a bit of further good news, the

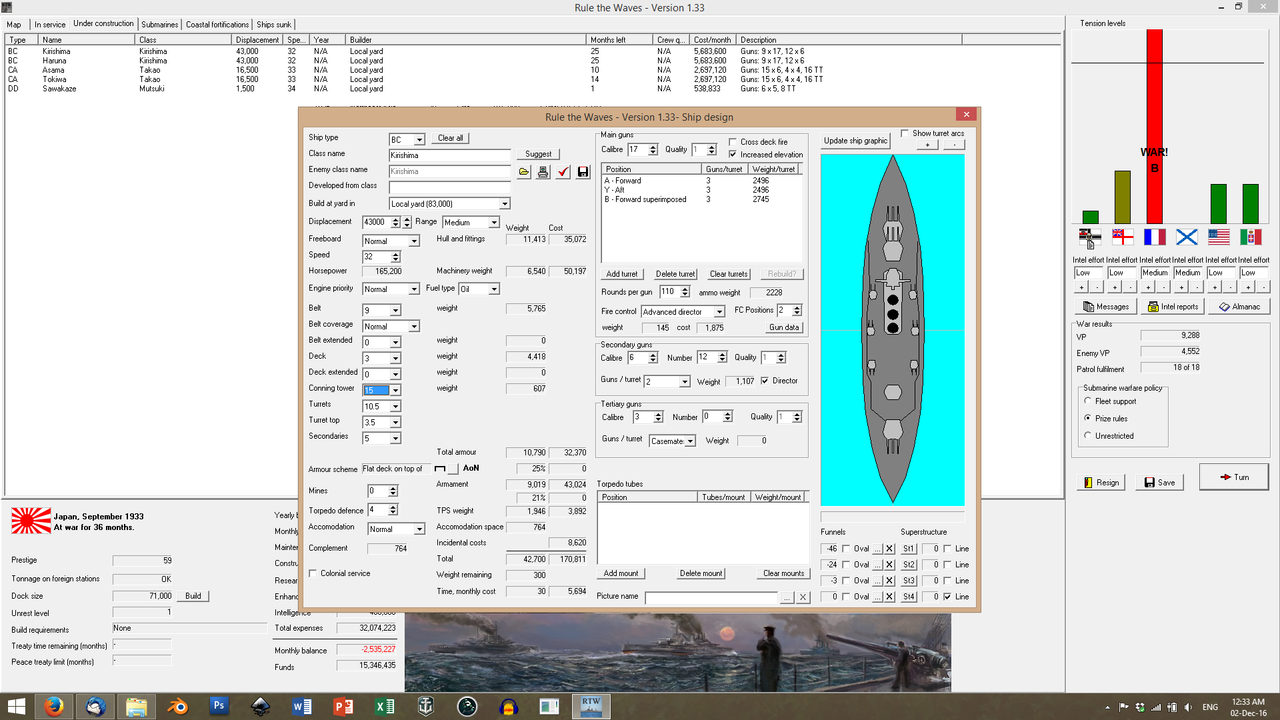

Hiei's exemplary performance had provided the necessary impetus for the laying down of her first two sisters:

Kirishima and

Haruna. The two new ships were, externally, almost perfect copies of their older sister, could reach the same staggering 32-knot top speed and mounted the same insane underwater protection. However, they were All-or-Nothing designs, which saved the engineers a

ridiculous amount of weight. That meant that, instead of the

Hiei's respectable world-leading 16-inchers, these ships would bear the Type 94B 17-inchers: the biggest and best naval rifles in the world, guided by the best fire control systems in the world. Lessons learned from the construction of the

Hiei brought their projected completion time to just over two years.

NO

NO, Fromage. You are going down.

-END PART 5-

{No Update Tomorrow because RL and family}

Poll

Poll