.png)

In early September, the R & D department delivered another groundbreaking development: a viable system for superfiring turrets. The stresses applied to the hull of the ship made it impossible (still) to have a front-mounted 'B' superfiring turret, but an 'X' superfiring turret, pointed toward the rear of the ship was well within the capabilities of Japanese engineering.

.png)

.png)

The Admiralty responded with a change in research doctrine. It was clear that Japan would never rival the production capabilities of giants such as Great Britain or the US. In the (hopefully avoidable) situation where she would have to meet their dreadnoughts in battle, it was, therefore, imperative that she hold a qualitative advantage. She needed a small core of

tough ships, with a decent punch, which could be relied upon to survive any but the most disastrous beating and come back swinging.

The R & D department was, therefore, asked to focus their efforts on damage control and torpedo protection, which they did, with gusto.

.png)

The Admiralty also considered several hypothetical designs for an improved

Ikoma-style battlecruiser at the time. The one the Admiralty felt held the most promise was the one codenamed

Kurama; but it was concluded that the weight requirements of a modern torpedo defense system would overwhelm both the current budget

and the shipbuilding capabilities of the Japanese shipyards. More time to build up infrastructure was needed - the Admiralty

refused to compromise and lay down a ship that would be obsolete two months after work on it had started.

.png)

Instead, further expansion of the docks was ordered; and experts were summoned to form think tanks on how to better miniaturise and implement the R & D department's findings.

.png)

.png)

The work of military intelligence confirmed that the Admiralty's new doctrine could be viable. On October, the blueprints of the Russian battlecruiser

Navarin found their way to the Admiralty, via a rather...complicated route. In short, the Russian ship had been laid down almost a year after

Tsukuba, but was still its inferior in everything but gun caliber - and Tsukuba was

designed to take hits from 12'' guns and keep on going. Drawing a comparison to

Ikoma was laughable - the Japanese warship would

tear through the Russian's belt armour in only a few salvos. Clearly, Russia was not a force to be feared - yet.

.png)

November was marked by further torpedo technology developments that had the destroyer captains champing at the bit for their new

Matsukazes.

.png)

It also marked the beginning of the Java crisis, one of the more contentious issues, that would mark the diplomativ arena in South-East Asia for the next decade.

Germany, with her original bid to weaken the French presence in the region having failed because of the quick Franco-Japanese peace, adopted a more aggressive stance. A task force was dispatched to occupy neutral Java who, while not an official partner or ally of Japan, played an important part in the diplomatic balance of the South China Sea and had even expressed interest in formally joining the Japanese Alliance.

The Japanese response could best be described as 'stunned'. There was much discussion on what stance to assume. It was important to keep Germany out of South-East Asia, from where she had been expulsed during the 1905 war; but it was also important not to appear imperialistic in the region and potentially sour the chance for a closer relationship with the USA. Finally, after long deliberation and discussion it was agreed that an international force should be assembled and dispatched, under a joint Japanese and USA command, to convince the German forces to back down.

.png)

The Germans did not; and the task force, under partially conflicting orders and the timorous leadership of cautious US diplomats did not offer further challenge. However, two things were made clear:

Firstly, the Germans and their long-reaching imperialistic ambitions in the Far East were still very much a threat to the stability of the region and Japan's interests.

Secondly, the Japanese had demonstrated that they had

no aggressive imperialistic designs of their own and that they were willing to operate in collaboration with other world powers; America in particular. As the US had also felt their bases in the Pacific to be threatened, this considerably improved the spirit of collaboration between the two countries; the term 'Pacific Neighbours' was coined after the Javan Crisis to describe the very cordial relationship between the two countries.

In short, Japan lost a potential protectorate and another base in the South-China Sea; but she earned herself a very close friend in the US and emerged the clear moral victor of the Crisis in the international stage, while Germany was almost universally villified.

.png)

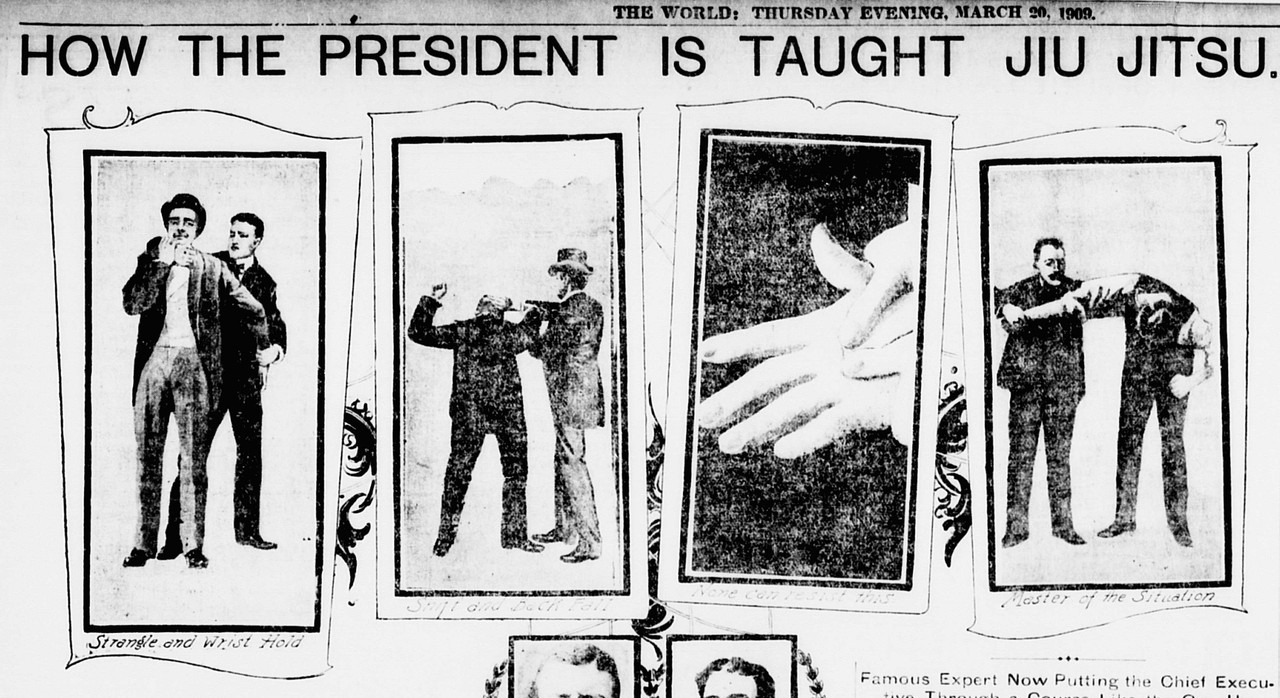

As a sidenote: the 'Japanese Craze' which took off in the USA during that period (most notable being President Roosevelt traveling to Japan to learn Jujitsu and Kendo from native tutors and the 'Sushi Mania' of 1909) is genuinely one of the most hilarious periods of the two countries' history.

(OOC Note: the above are actual things and the images have only had the dates changed, holy crap, the silliness is overwhelming)

(OOC Note: the above are actual things and the images have only had the dates changed, holy crap, the silliness is overwhelming)Also:

.png) ****ING FINALLY. SPAGHETTIS GO HOME, I HAVE BETTER FRIENDS NOW.

****ING FINALLY. SPAGHETTIS GO HOME, I HAVE BETTER FRIENDS NOW..png)

On Christmas day of 1908, the first of the

Matsukazes,

Minazuki was commissioned into the Navy. She immediately started her shakedown cruise and was much praised by her crew for her high top speed and her increased stability and high freeboard.

.png)

The Russian Navy also made a half-hearted attempt to acquire the licence to the Japanese oil-fired boilers design. They were calmly and politely shown the door: if Japan was to maintain her qualitative advantage over her enemies, she would have to keep such critical technology classified.

.png)

(OOC: Why, yes, Italy, I have no objection to

selling you a

crappy firing control sub-tech. *CASH REGISTER SOUND*)

.png)

No, the Japanese Navy had no objection to selling off what it considered to be less-important advances,

especially when their engineers had just further opened the gap with the installation of high-quality 9ft-rangefinders on every Japanese ship.

.png)

And then, Intelligence delivered again, by securing the prototype blueprints for the British

Invincible battlecruisers -

Tsukuba's older sisters.

.png)

In their defense, they mounted 13'' guns, which could give

Tsukuba's 10'' armor trouble at close range. But they were also horrendously underarmoured compared to her, with a 6'' belt. Tsukuba's 11'' guns would go through that belt like a hot knife through butter, at

any range; and any hit to the Brits' vulnerable engine room would rob them of their speed - a crucial element for the survivability and effectiveness of a battlecruiser.

As for Ikoma - she would be slower, true. But in any broadside engagement she was sure to turn the British ships into swiss cheese.

In short:

Poll

Poll