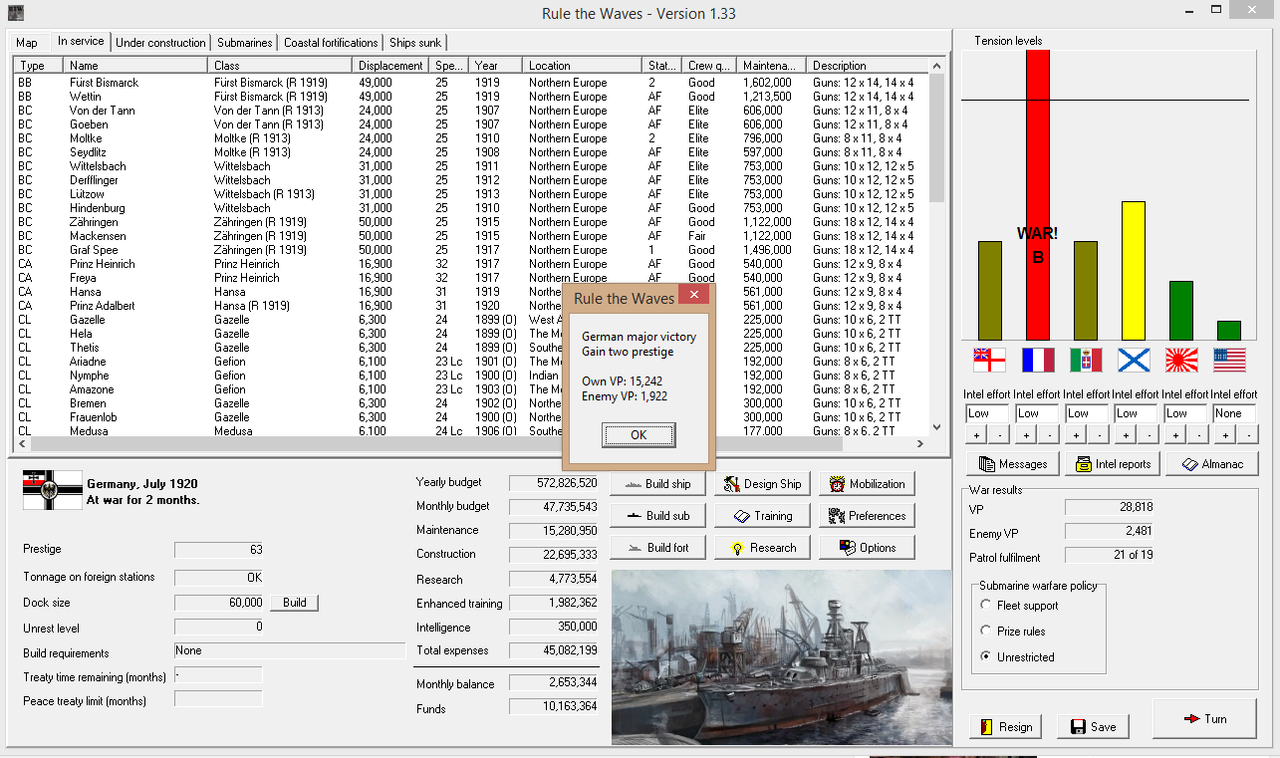

Names, lives and individuals are unimportant when Germany's final fate is at stake.

Names, lives and individuals are unimportant when Germany's final fate is at stake.-From the personal notes of Franz von Papen, quoted in Piotr Fiyodorowski The French Matter, Berlin : Hauser Vlg. 1958

Hindenburg is ready to tear his mustache off at the

utter incompetence of his new Chancellor. Germany's wars live and die by

preparation; by having a plan, by communicating and by allowing the military to draw up a satisfactory strategy before pulling the metaphorical trigger. This has

not taken place here. Certainly, war with France was a very real danger, that the military was making preparations against - but nobody expected a war

this soon. The Army is

not fully mobilised; the Navy is still in its harbours.

For a few days, Hindenburg lives in a

nightmare, certain that what he will have to deal with is a reversal of 1870. But the French, surprisingly, seem to be as unprepared as the Germans, and they do not press their advantage. As the regiments reinforce the defensive line against the border, Hindenburg reaches out to the Navy. Out of all the German armed forces, they are at the highest readiness status. They

need to buy him time; they

need to push the French and regain the initiative; keep the enemy's attention focused on them, while the Army gets its act together and prepares for an offensive.

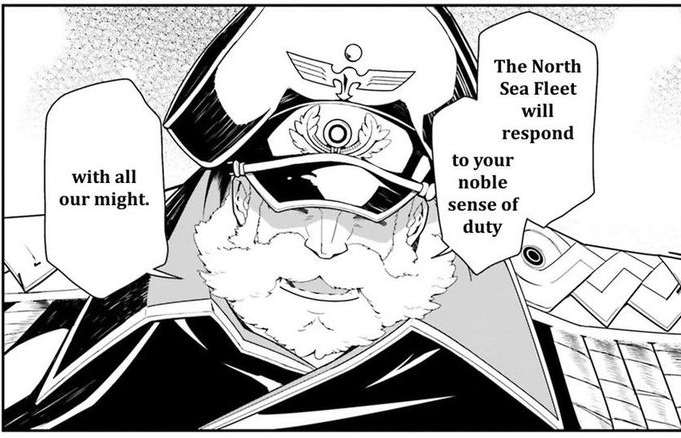

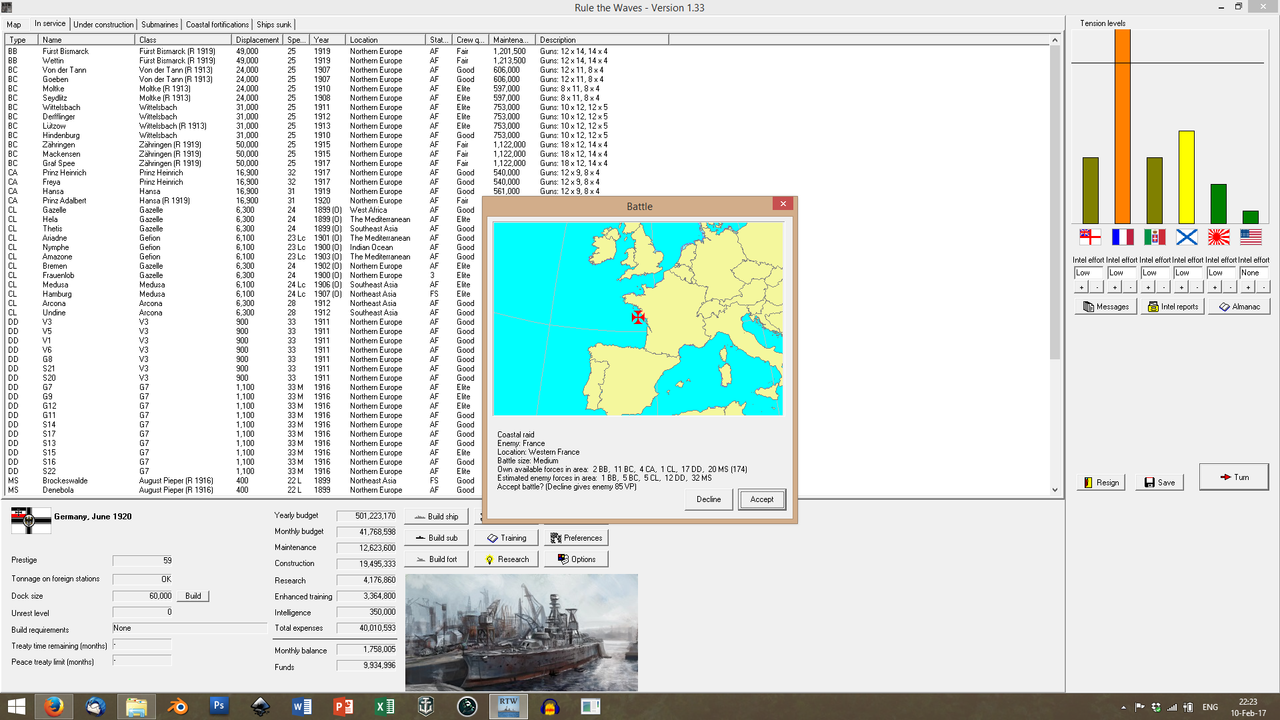

Galster responds by authorising a massive fleet patrol along the Dutch coast. Stresemann backs him by outright declaring that Germany will guarantee Dutch neutrality; and her fleet is on station to block the eastern mouth of the English Channel.

The British Fleet cowers in its harbours, as the

Zähringens sail out...

...and so do the French. The Netherlands are safe, under the protection of the German

Schlachtkreuzergeschwader. Now for Belgium...

The

Admiralität takes advantage of securing the North Sea to sail in several large resupply convoys.

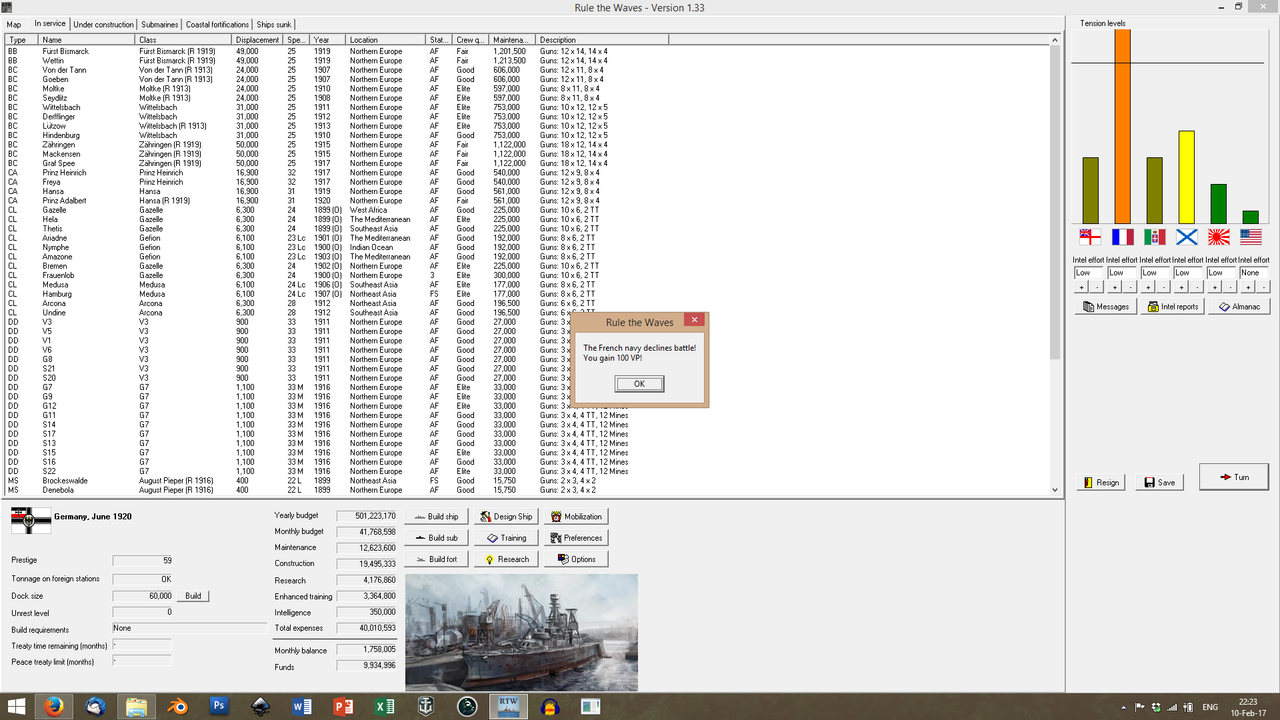

The French do not dare to leave their ports.

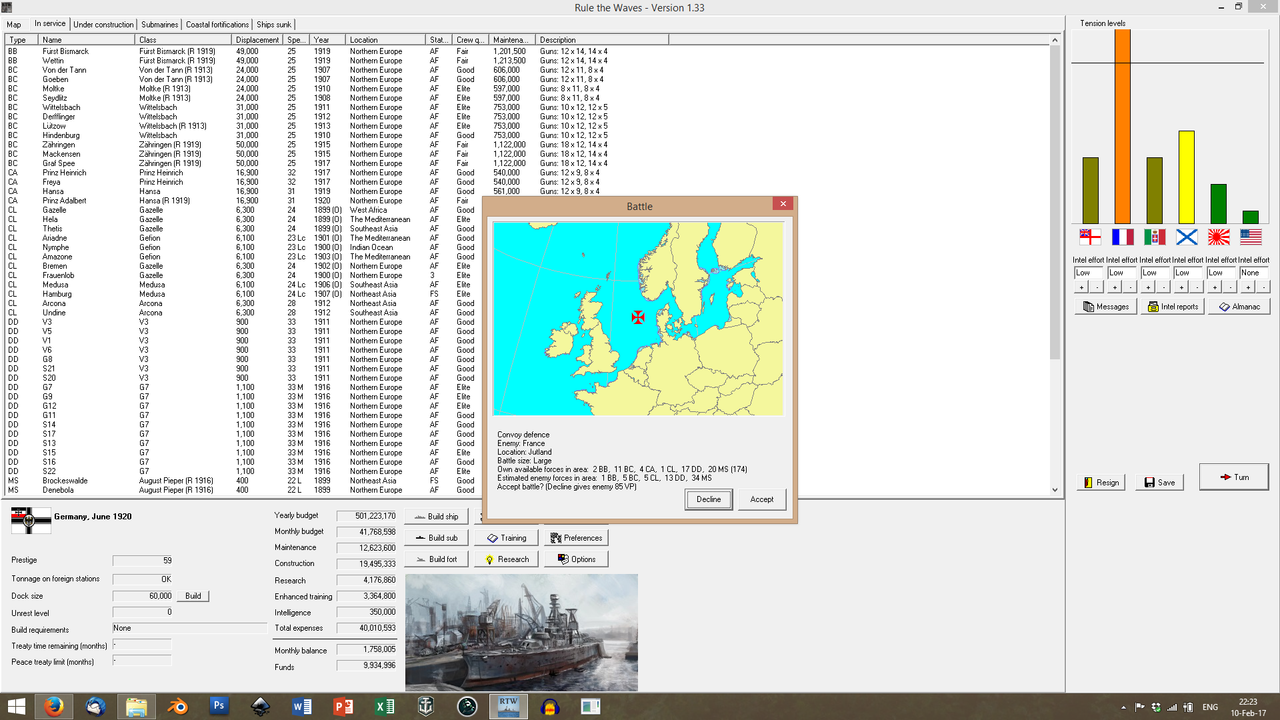

This is not enough for Galster. He

needs to draw the attention of the French High Command; he

needs to present them with a challenge that they

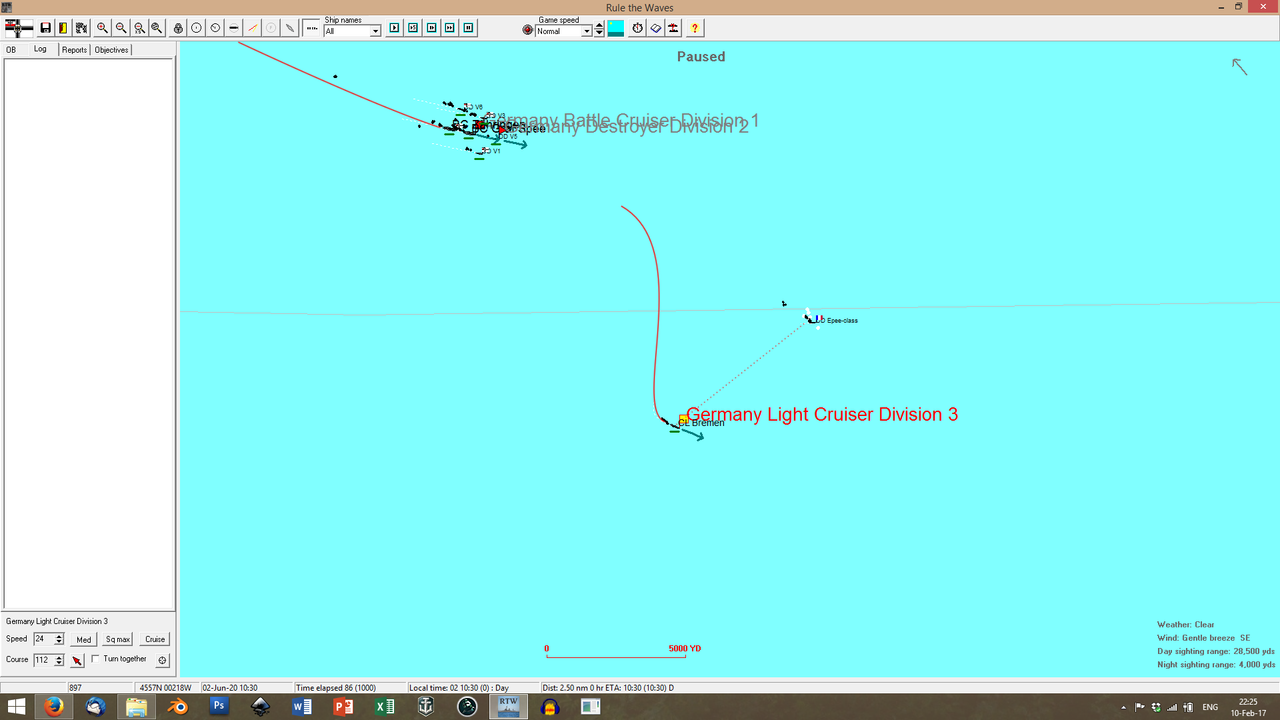

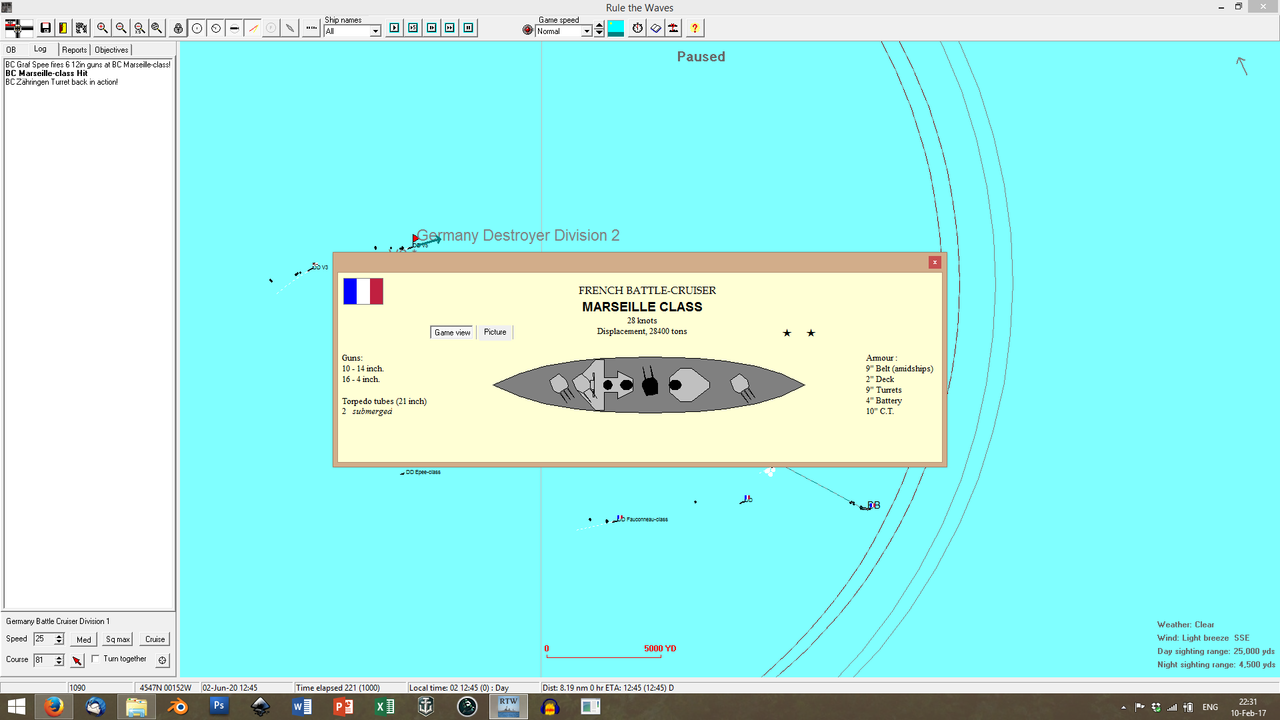

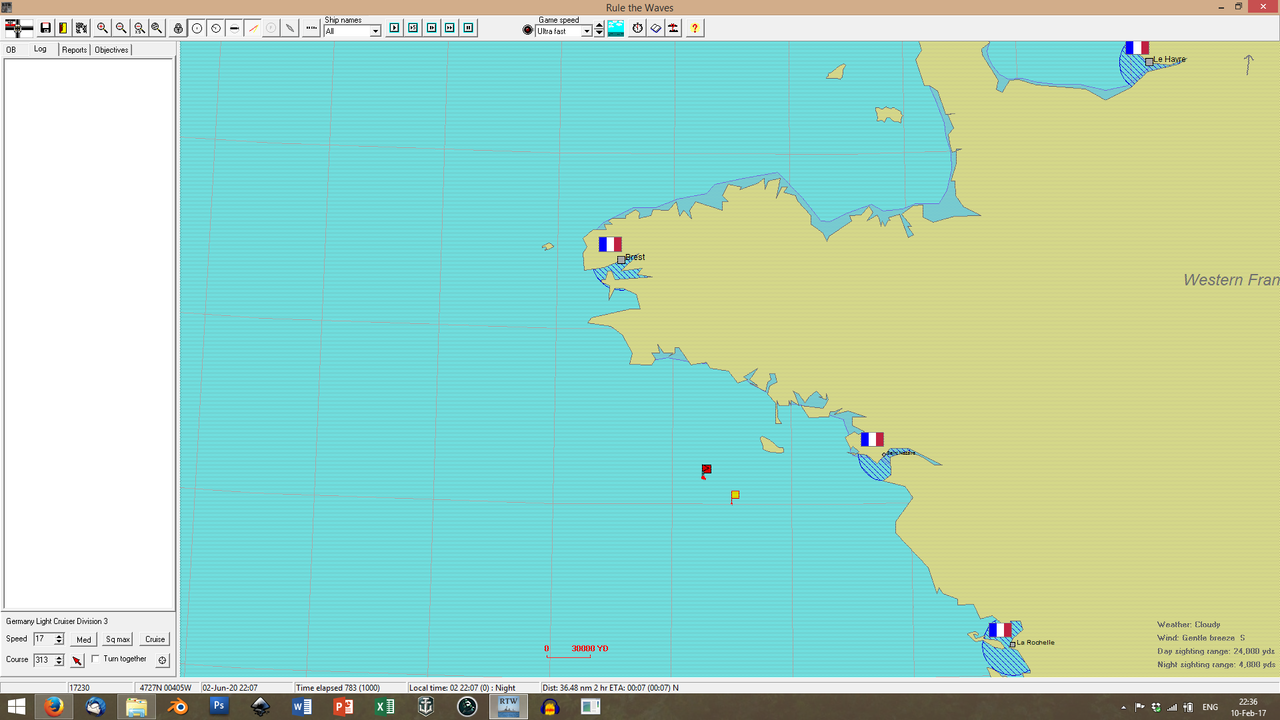

must respond to. So, on the 2nd of June, the

Zähringen and the

Graf Spee, escorted by the

Bremen, sail past the French garrisons in Armorique and enter the coastal waters of La Rochelle. It is a flagrant challenge; a contemptuous slap on the face of the French; and the French

finally respond.

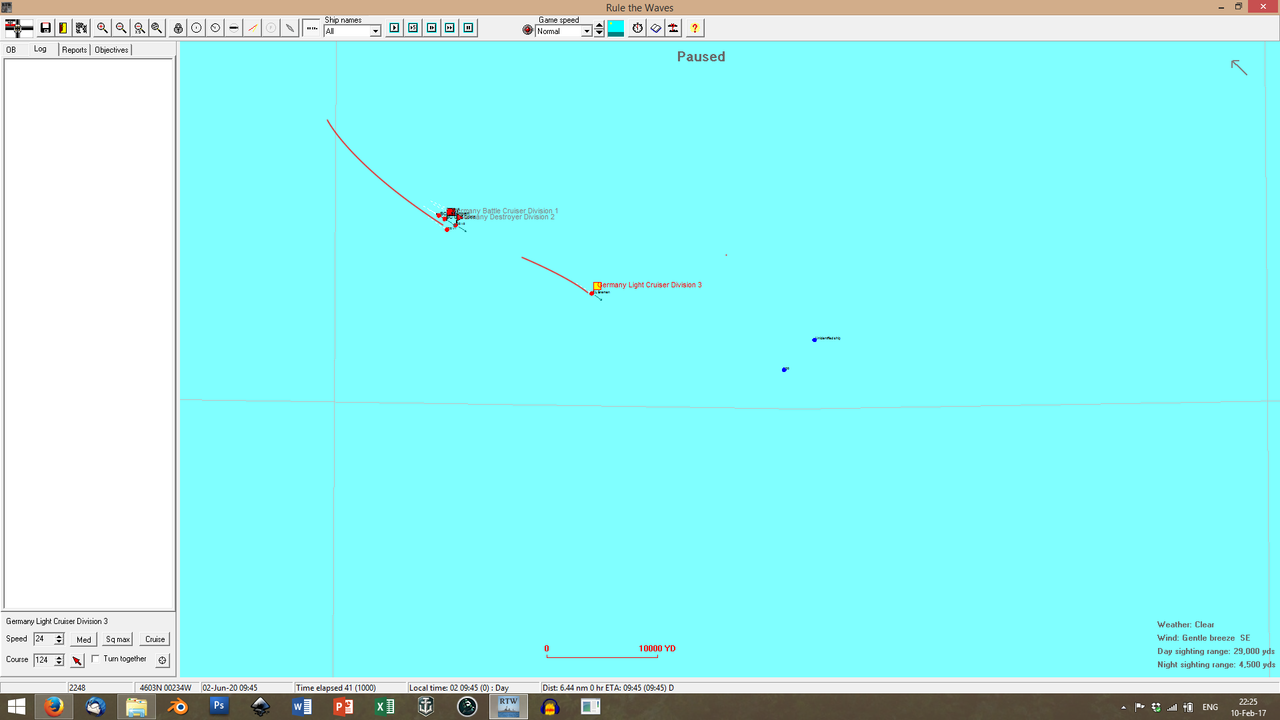

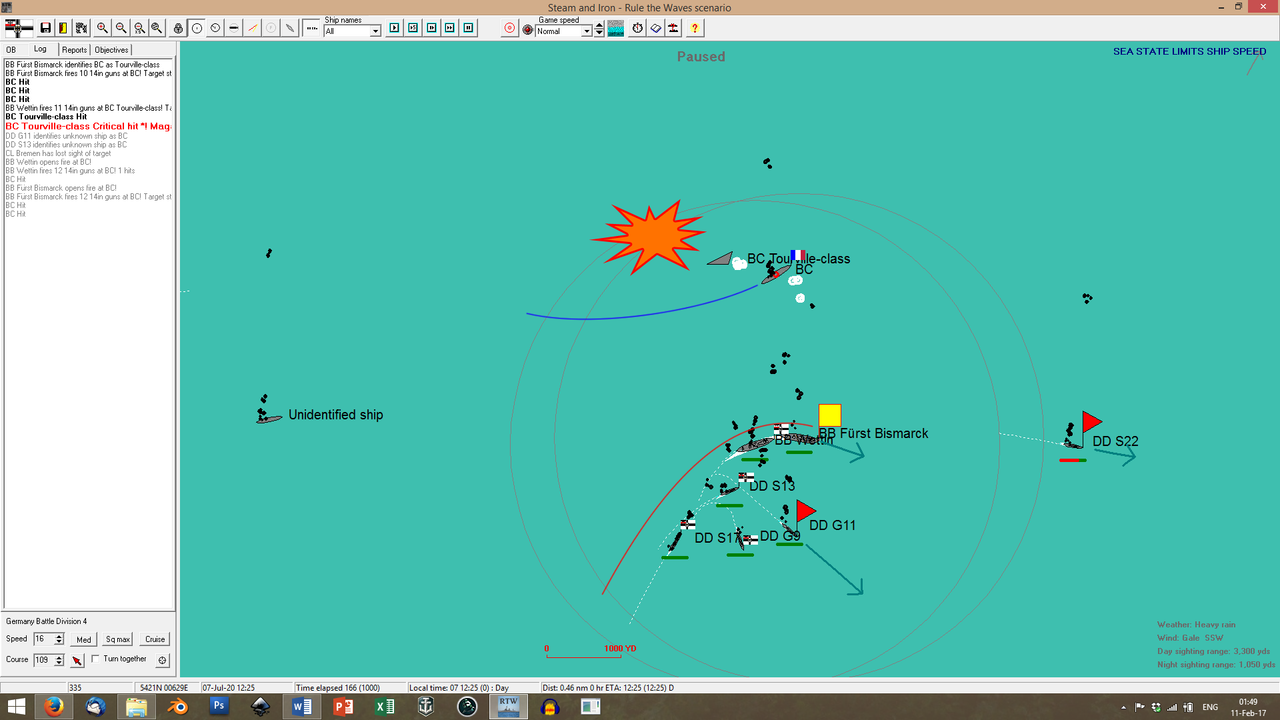

9:45am, and the

Bremen, approaching the French coastline from the North-West, spots enemy smoke. At least two ships; and one of them is a capital. Behind her, Hipper, on board the

Graf Spee, rouses his crew to action stations; alarms blare loud enough to wake the dead.

Bremen

Bremen, captained by

Fregattenkapitän Markus Vogler safely identifies the nearest ship as an

Epée-class destroyer. She's laying smoke, to conceal her allies; Vogler opens fire against her with

Bremen's 6-inchers, as the

Schlachtkreuzer charge in.

The French destroyer is driven away, and the German capital ships push through her smoke screen, spotting a French light cruiser and...two more ships (?) in the distance. The lookouts are uncertain; gunnery, for now, focuses on the French cruiser.

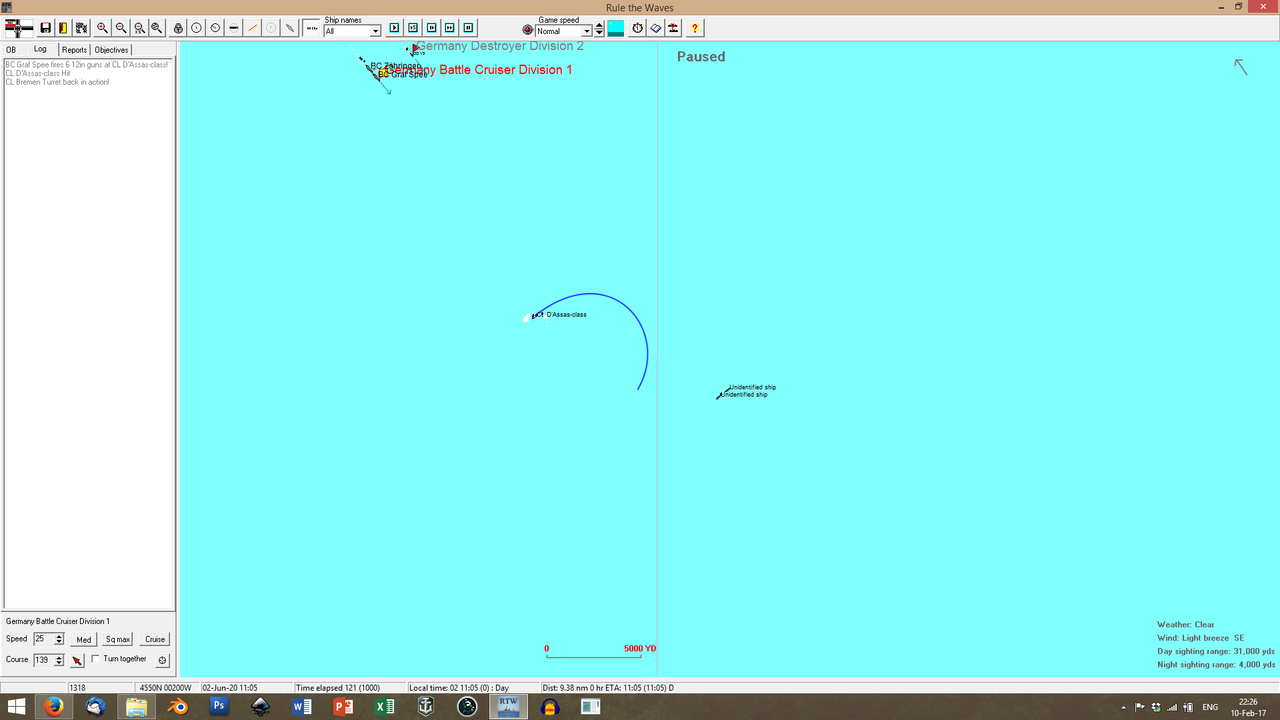

But then the

Bremen rejoins the fleet, the

Epée safely driven off, and her veteran lookouts identify the enemy ships as capitals. Specifically, two

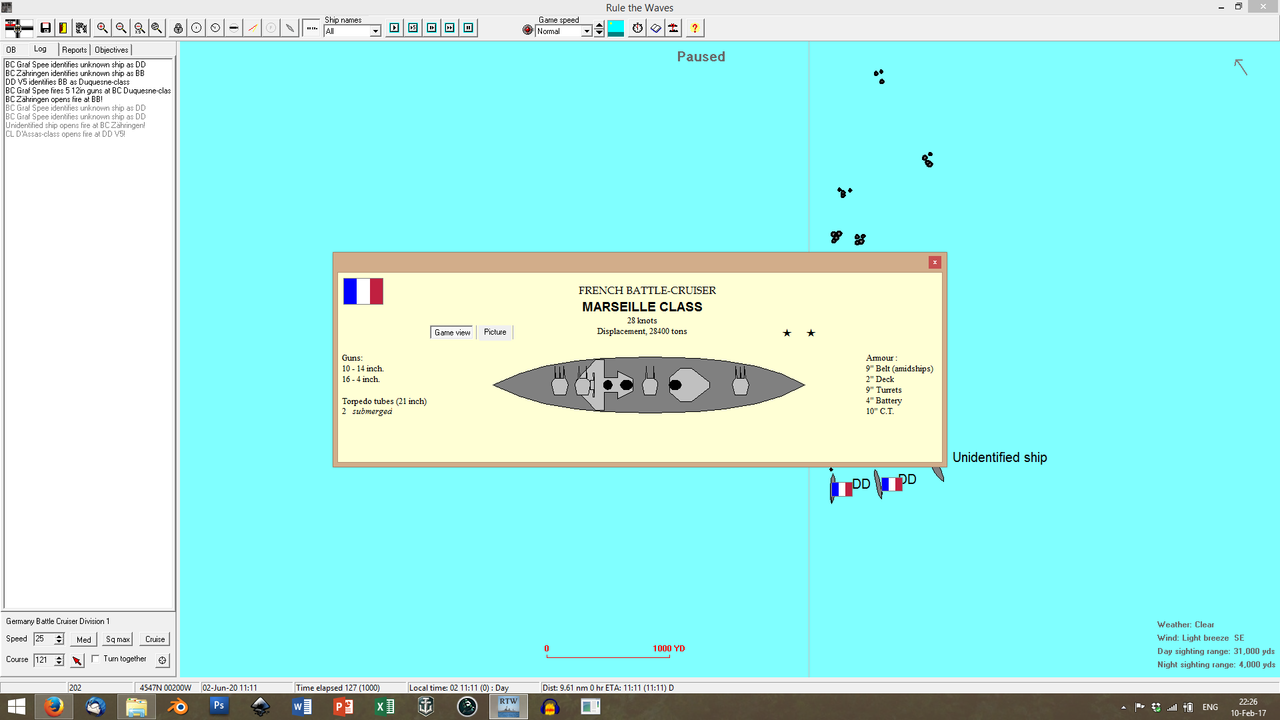

Marseille-class 14-inch battlecruisers closing from the south...

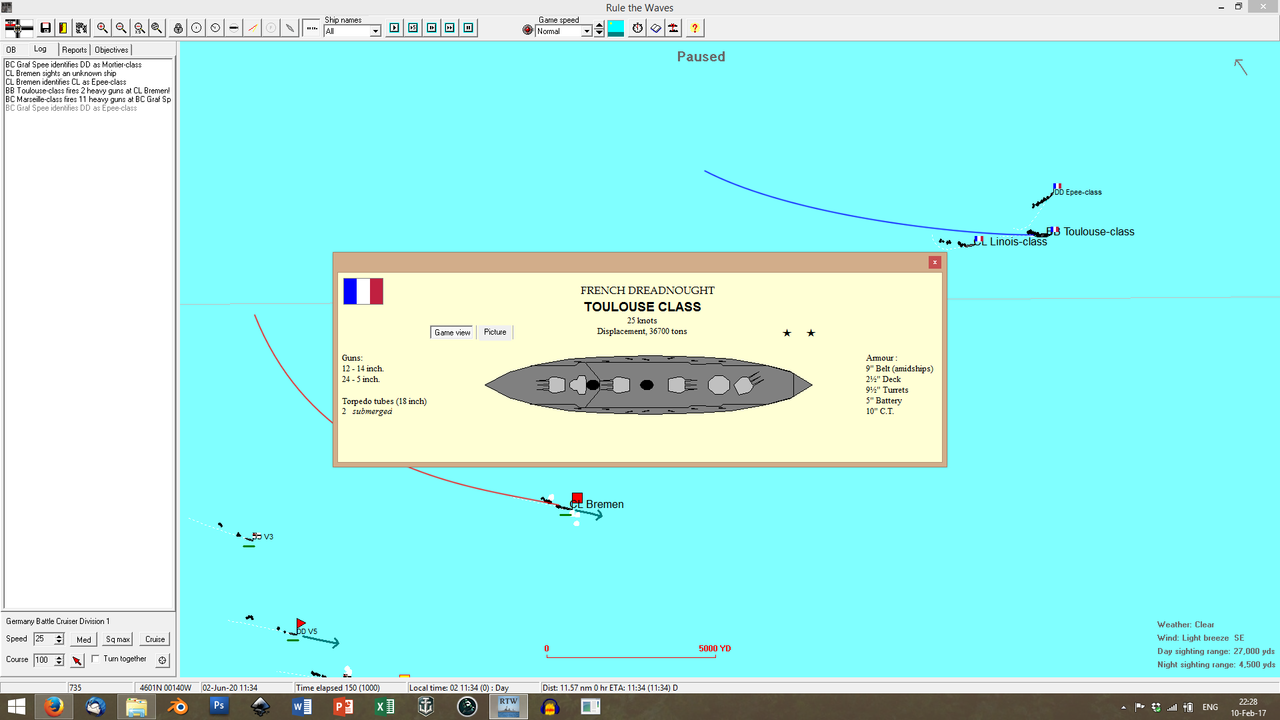

And a French

Toulouse-class 36k-ton dreadnought approaching from the north. Holy crap. OK, this thing has only a 9-inch belt, but it carries

12 14-inchers, as many as the

Bismarcks...

Hipper doesn't give a flying ****. He has charged his ships into British 15-inch fire; it's not the French peashooters that will scare him.

SCHLACHTKREUZER RAN AN DEN FEIND!

SCHLACHTKREUZER RAN AN DEN FEIND!

The German ships turn, to pursue the French battlecruisers. They are

slower than the enemy ships, but the French have, foolishly, allowed themselves to enter the range of the German 12-inchers.

Zähringen scores the first hit, from a range of over 20k yards. The new 15-foot rangefinders work

perfectly.

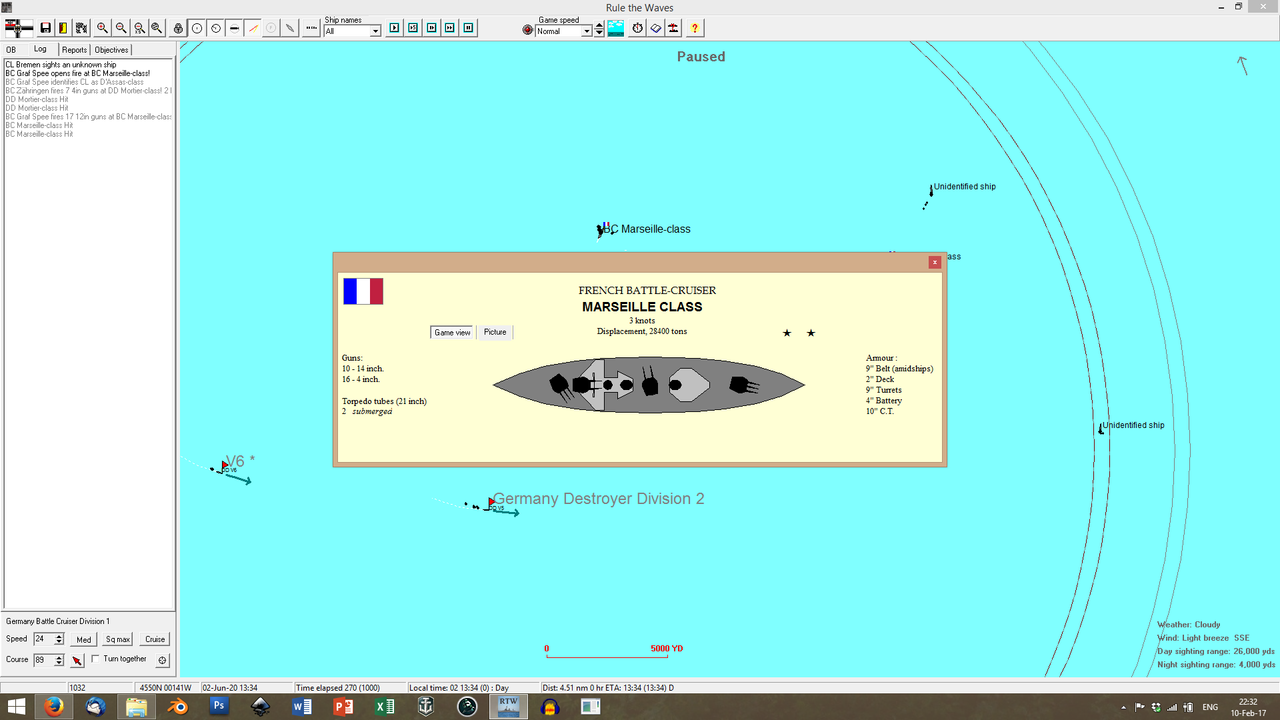

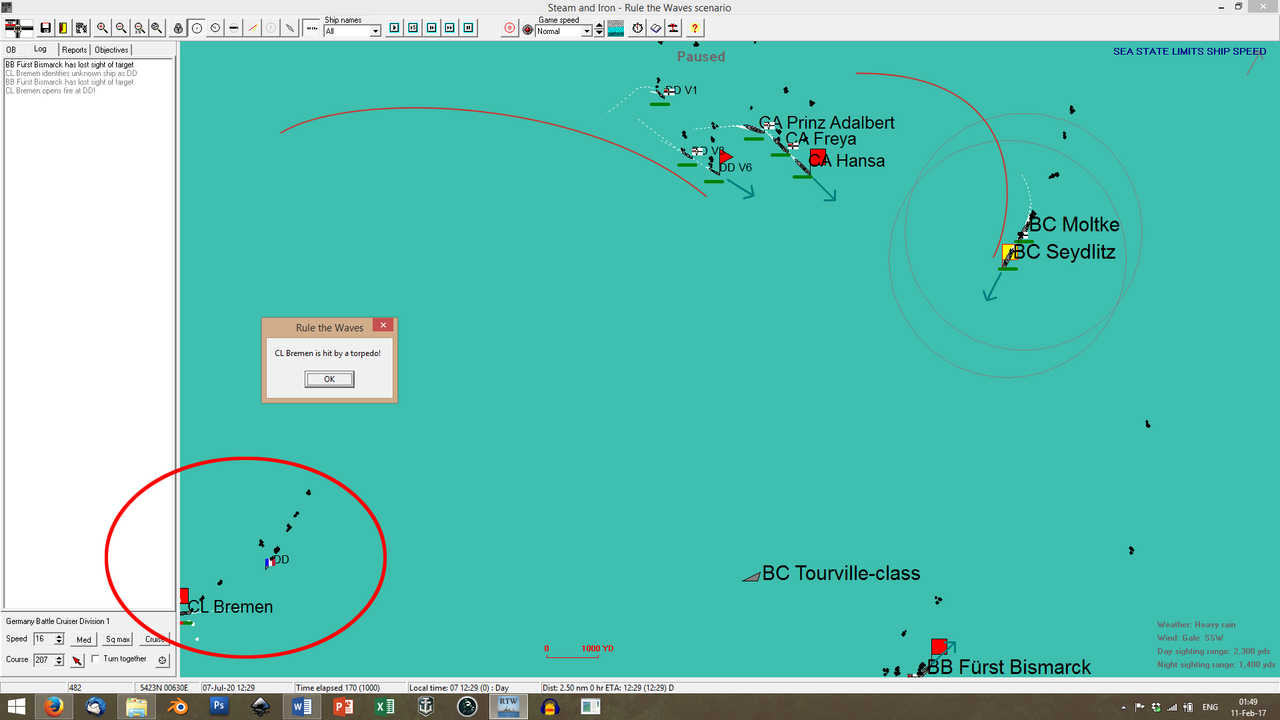

Meanwhile,

Bremen moves to the north, in a screening action. She drops smoke, that interferes with the

Toulouse's targeting. Hipper wants his duel with the French battlecruisers to remain uninterrupted; Vogler does his best to oblige him.

He succeeds. Oh

God does he succeed.

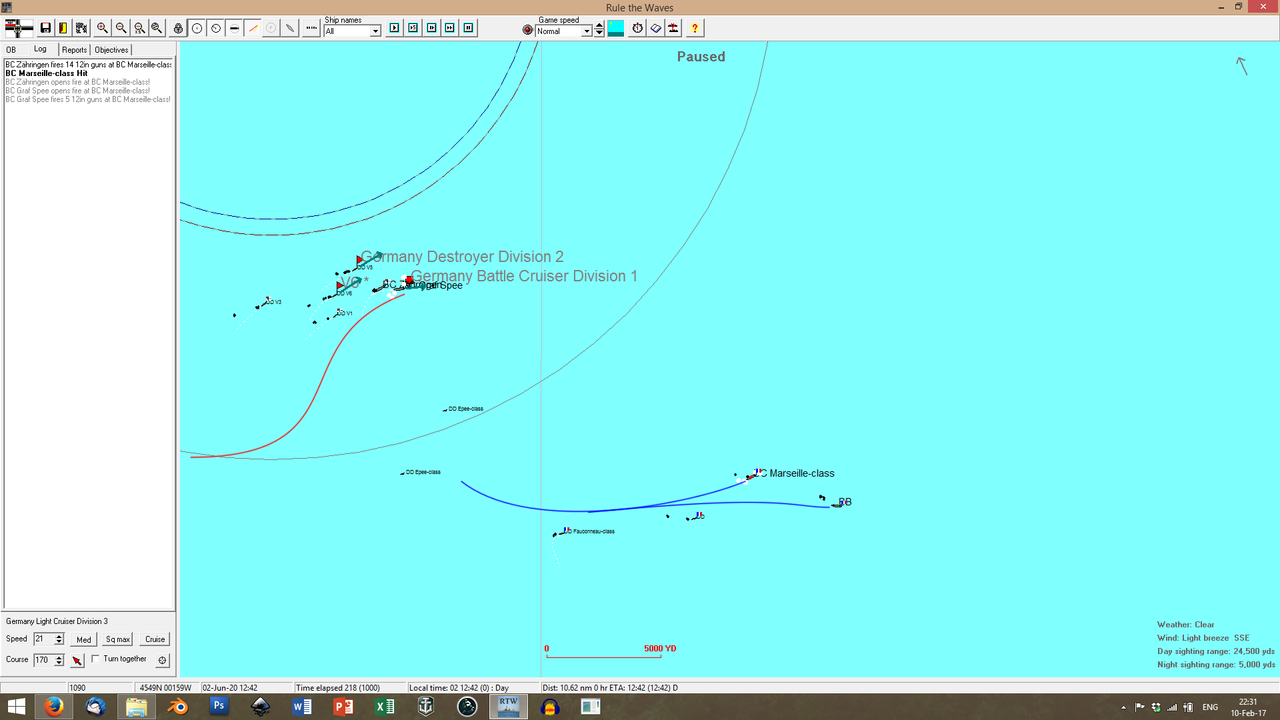

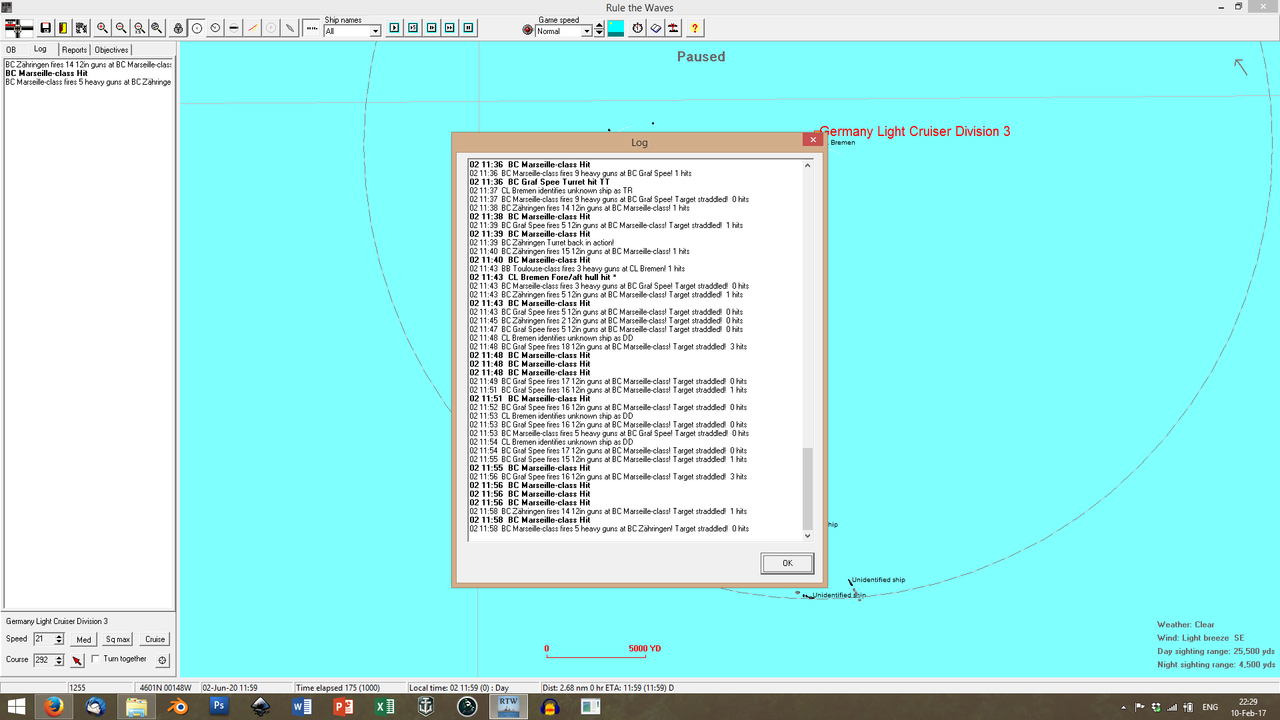

Over the course of twenty minutes, and while the French are still trying to find the range on the relentlessly charging German behemoths, the

Graf Spee and the

Zähringen lock on to the two

Marseilles and

pound them, mercilessly. Hipper knows that his time is precious, and orders double-time for the loaders; the

Schlachtkreuzer guns bark again and again and

again, a never-ending hail of steel, walking its way to the French ships. German fire control logs at least

fourteen 12-inch hits as the enemy tries to open the range. The French only score one hit, before they turn and run in terror; the 14-inch shell bounces harmlessly off the

Graf Spee's B-Turret top armour.

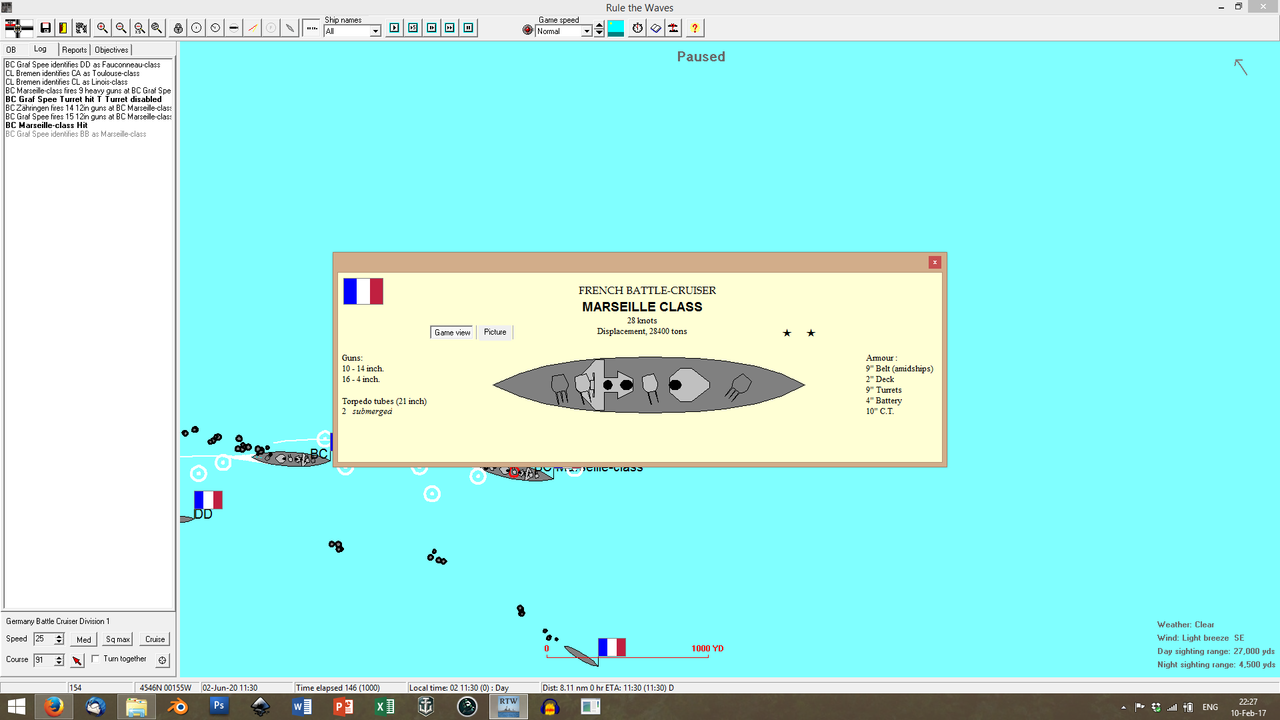

On the other hand, the

Bremen is not so lucky. As she seeks to keep the

Toulouse occupied, the French dreadnought scores a hit on her bows, smashing them to kindling. The ship staggers and falls back, barely responding to the wheel;

Zerstörer close in to lay smoke and cover her escape. She has suffered major casualties, but her crew (veterans one and all) manage to keep her in the fight.

Meanwhile, the two

Marseilles have been mauled. The leading ship has taken one major hit on her center turret, which has smashed through the turret armour and blown the entirety of the mounting off; the ship is trailing smoke and fire.

The

other ship (the one

Graf Spee has been favouring with her attention) is already

dead, all of her turrets blown to smithereens. French sailors are jumping overboard, as the ship develops a list to port and slowly, gracefully, capsizes.

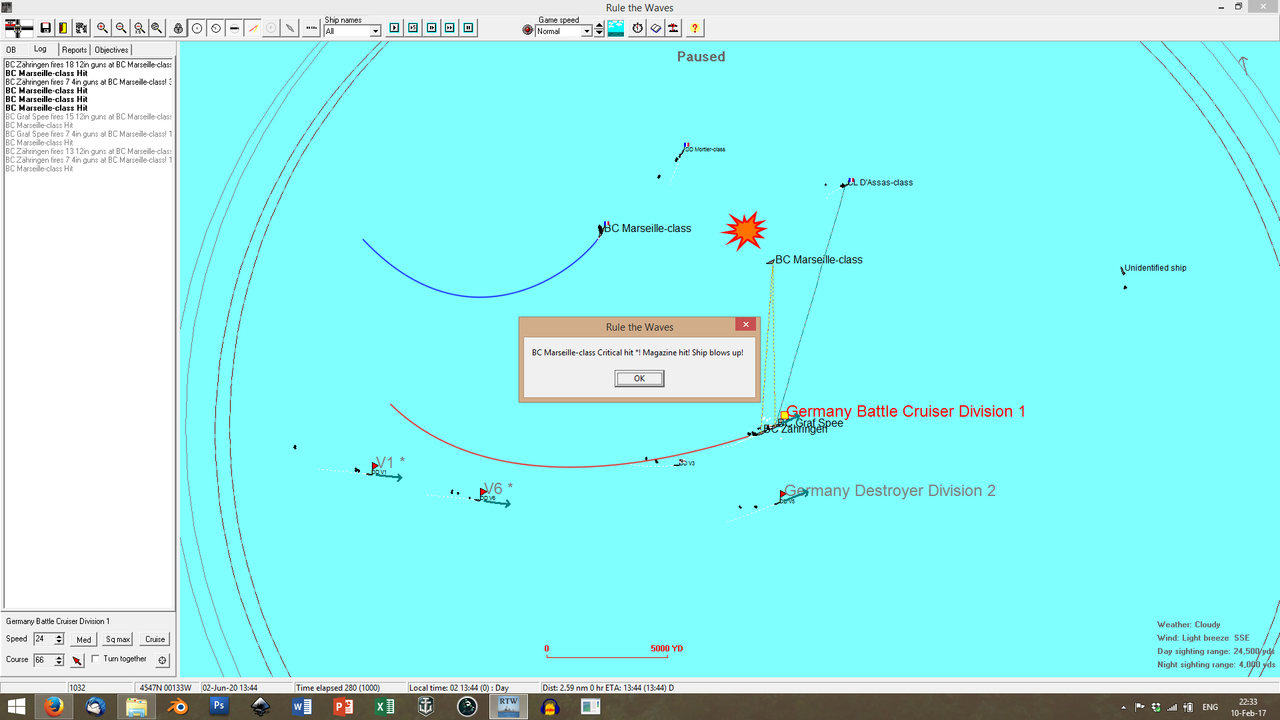

The German

Schlachtkreuzer overtake the enemy from the south and curve around towards the north, to keep the leading

Marseille under fire. Once again, the German ships demonstrate that they are in a class of their own.

Zähringen fires a broadside, at a range of 8k yards. One 12-inch shell strikes the

Marseille on the waterline, just behind her A-Turret...

...and the French ship goes up like a firecracker, her escorts scattering like headless chicken.

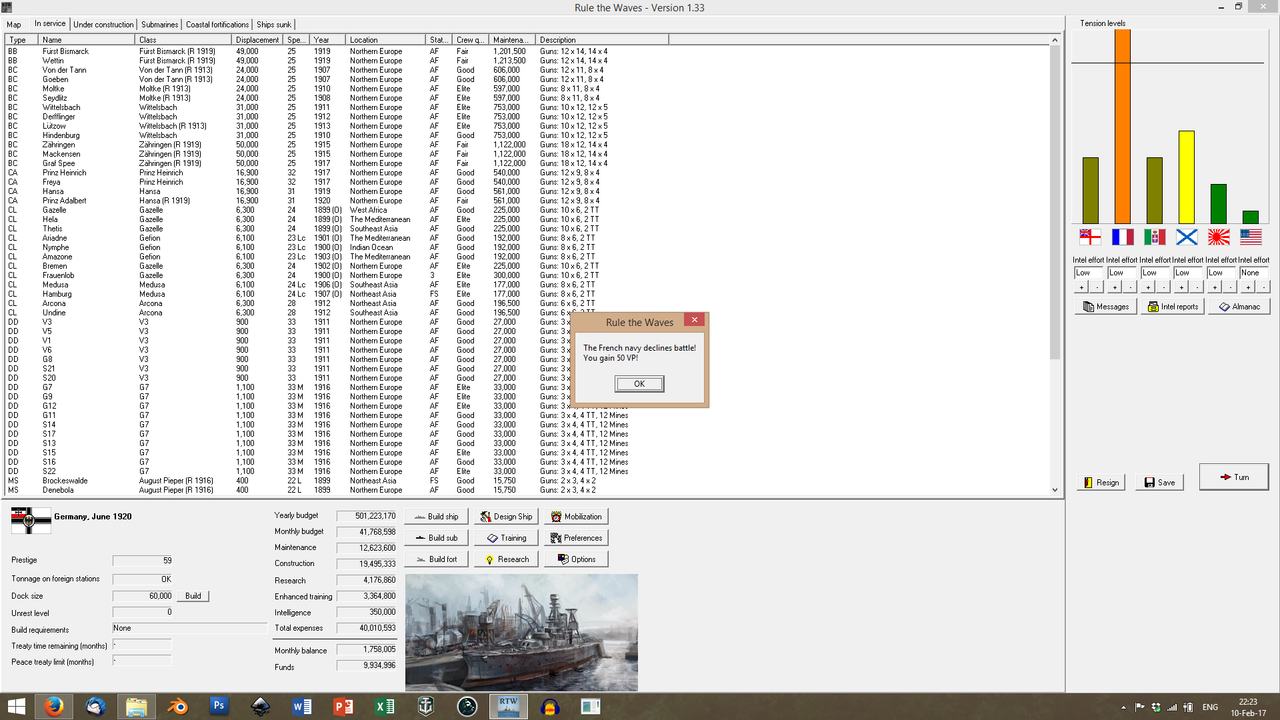

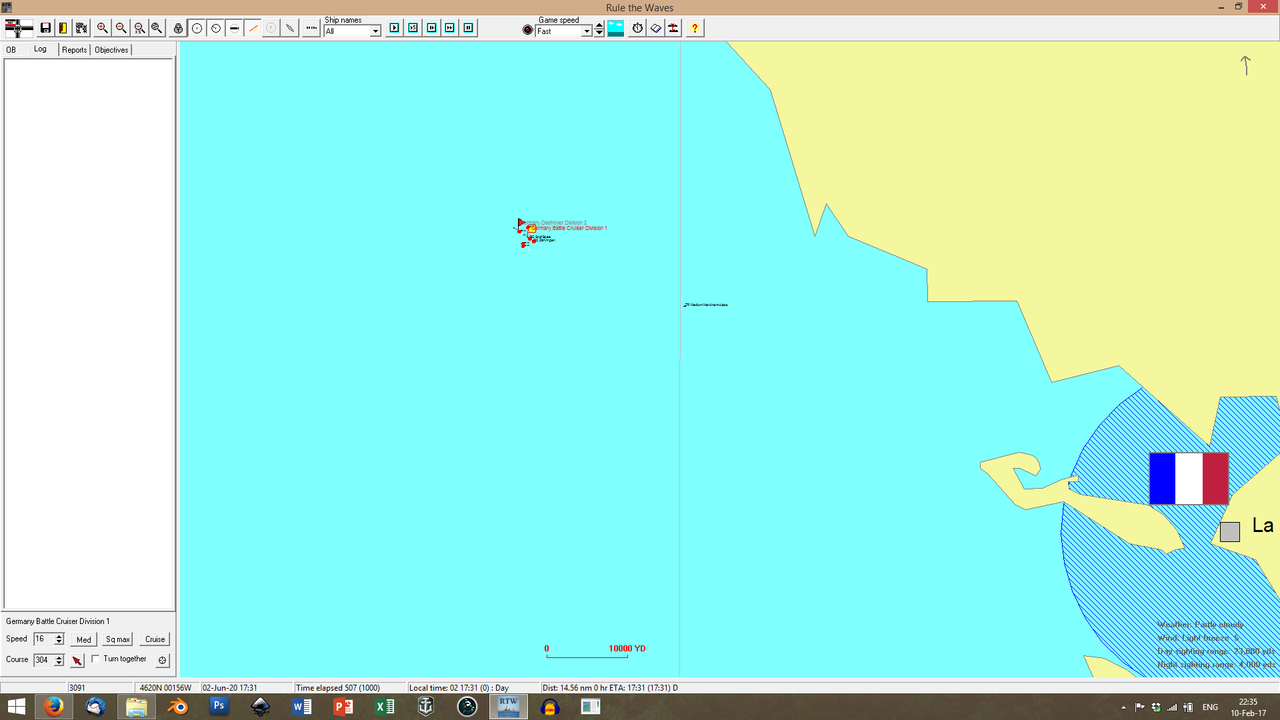

At this point, the

Toulouse is out of sight, somewhere behind the smokescreens to the north; and Hipper has no reason to pursue. This is a great victory, that

demands an answer from the French; his mission is accomplished. He turns to the north, leaving La Rochelle behind.

And uses nightfall to sneak past the French patrols near Brest.

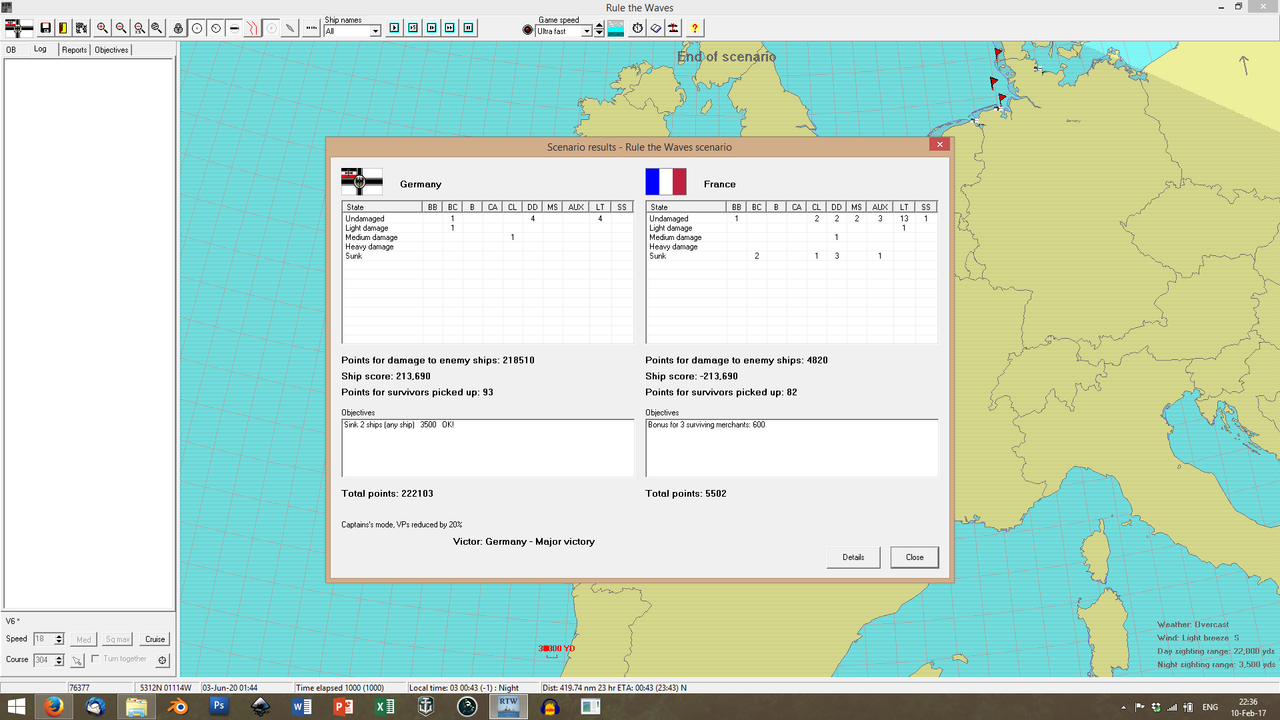

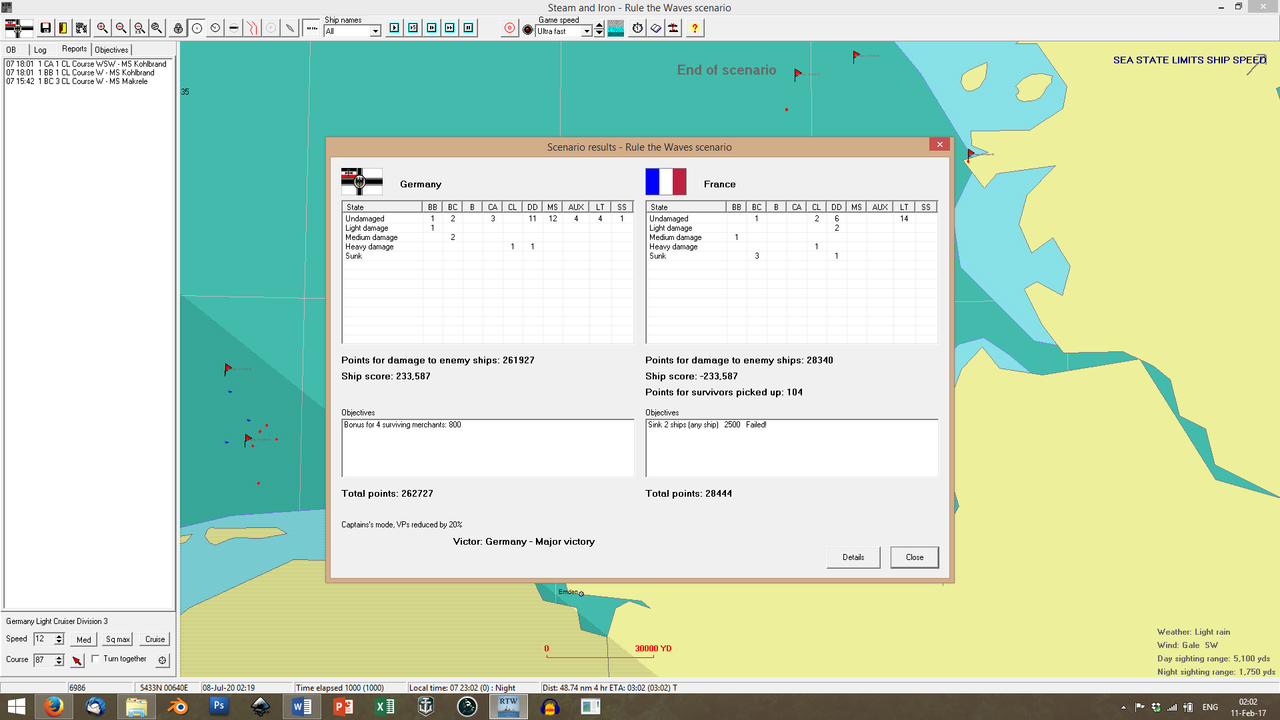

What a bloody victory!

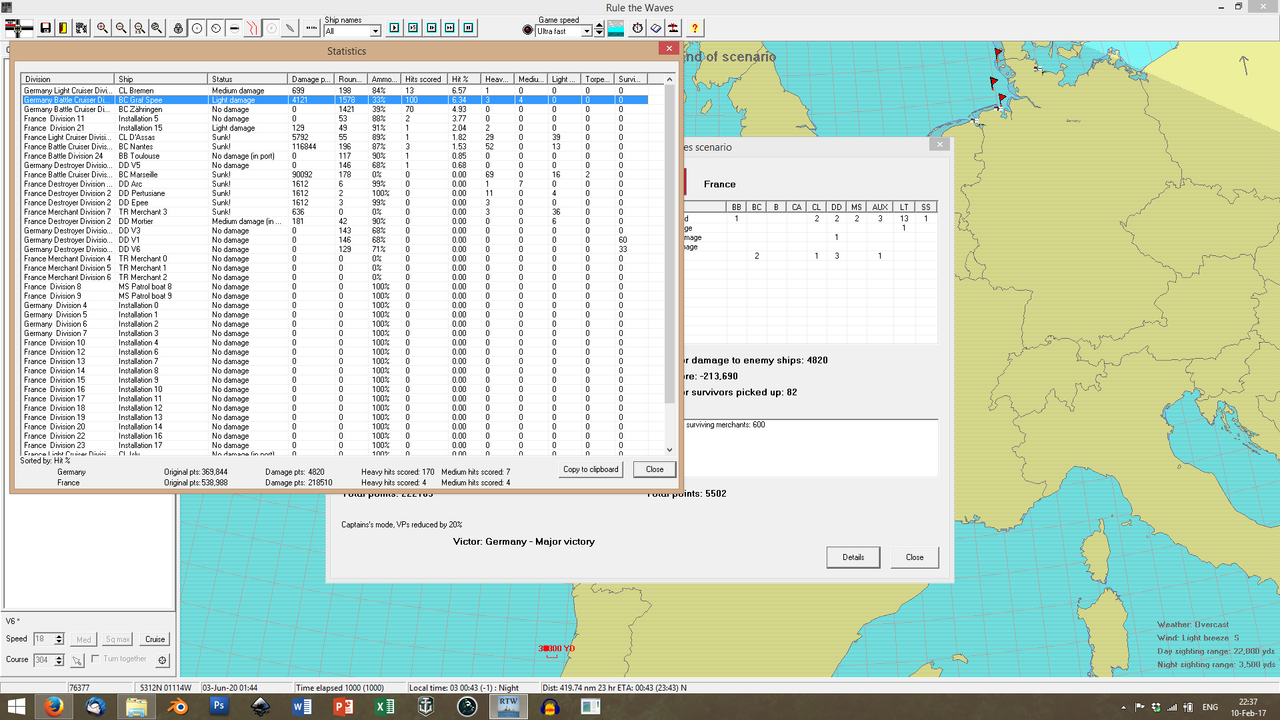

Out of all the ships participating in the fight, it is little

Bremen that scored the highest hit percentage, peppering the

Toulouse and enemy destroyers with high-explosive shells. But it is the two

Zähringens that have finally come into their element. Between them, they have scored (wait for it)

a hundred and seventy hits on their opponents, the German 12-inchers firing almost continuously throughout the engagement. In fact, upon her return,

Graf Spee immediately enters drydock, to have her guns re-bored, after the repeated use essentially destroyed their rifling.

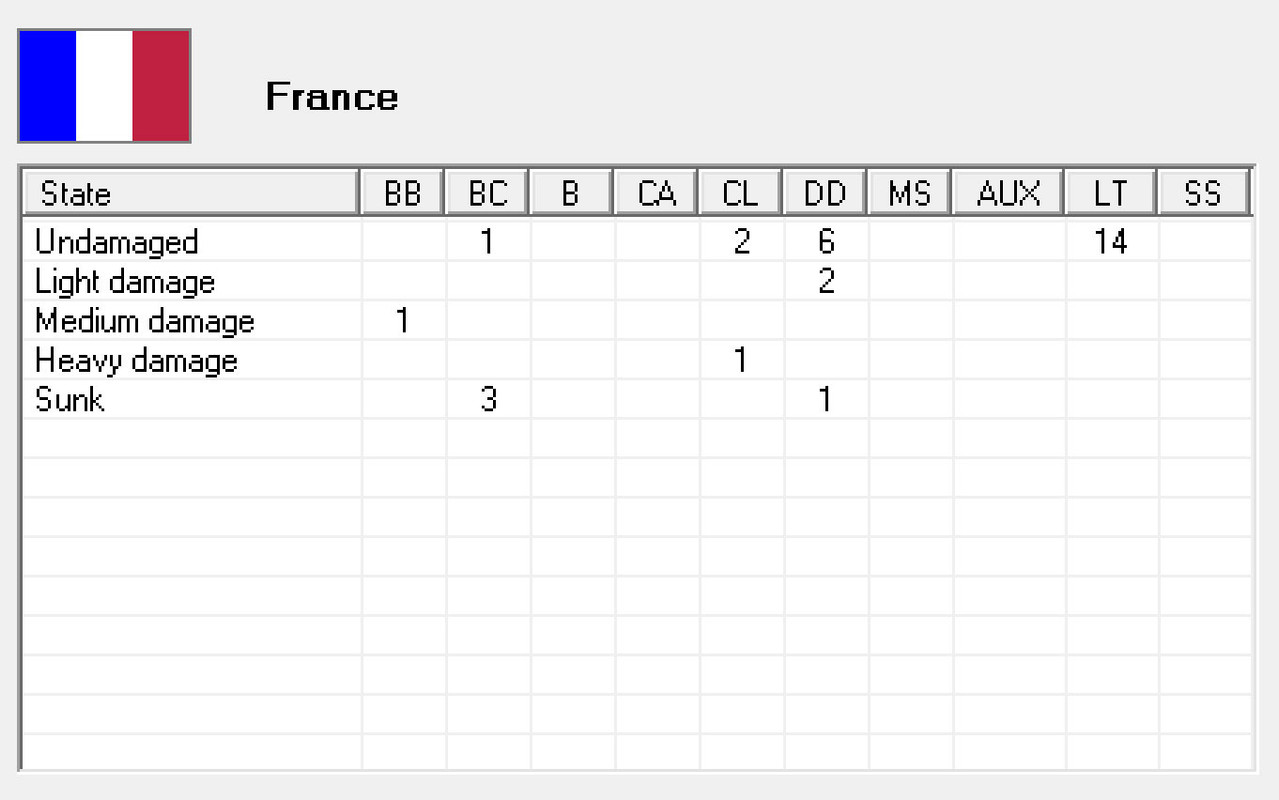

The French lose their two

Marseilles; the name ship herself and the

Nantes. The

Toulouse reached the safety of La Rochelle without suffering any significant damage.

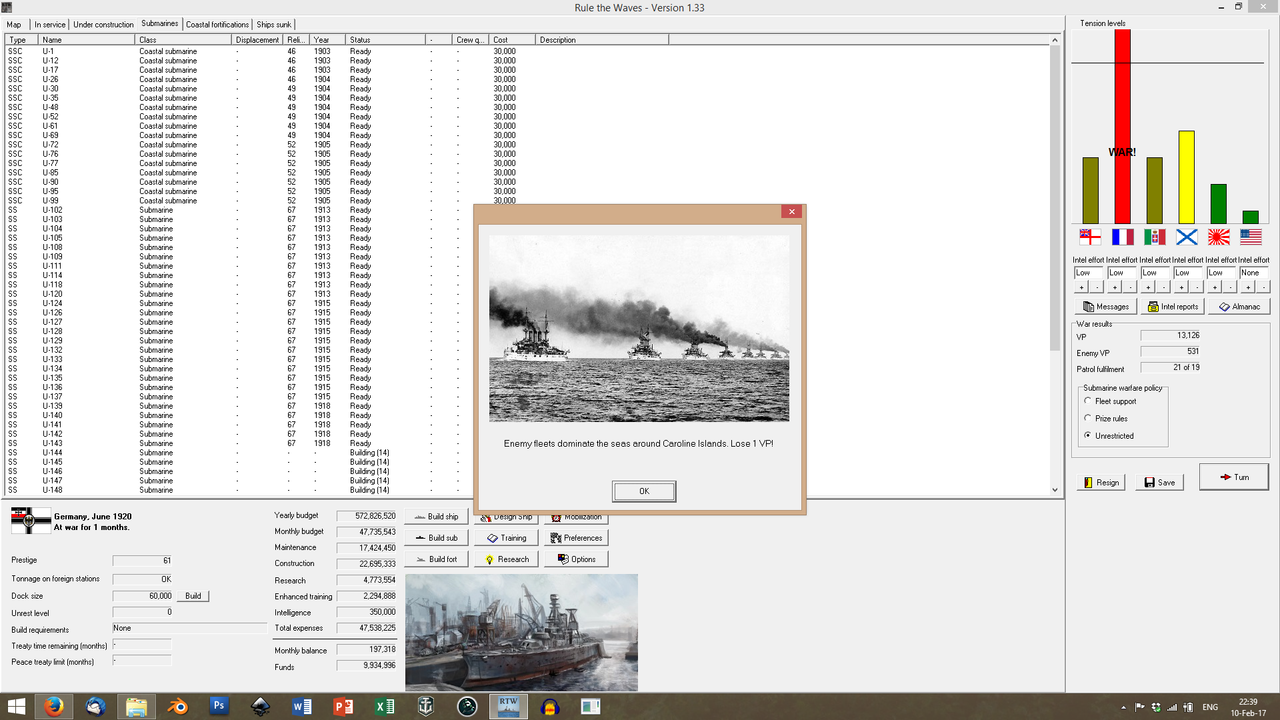

But, while von Papen rejoiced and trumpeted Hipper's success from the rooftops, the

Admiralität remained skeptical - and, surprisingly, so did the Kaiser. His Majesty now spent hours in the

Admiralität building, discussing with his officers; and, for the first time, he was actually

listening.

The situation was critical. The French did not possess the massive capital fleet of the Brits; but they

did have a significant raiding and submarine force; and whereas the Germans had concentrated their fleet in the Northern Atlantic, to make sure that the flow of supplies would continue to reach Germany unimpeded, the French had dispersed their forces around the world, skirmishing with German patrol forces all over the Pacific. This was an unsung war, hardly comparable with the large capital ship battles in the North Sea; but no less desperate and no less brutal. The

Piepers and

Zerstörer in German Polynesia had their hands full, dealing with French raiders and submarines, not to mention the infamous

Aigle and

Herrault, the two 4k-ton French light cruisers that utterly dominated the Pacific; the

Admiralität was very much aware that the situation there was hanging from a very fine thread indeed.

OK. R & D? We love you, and we very much appreciate your hard work. But we are

no longer building light cruisers. When we want to kill things in the high seas...?

...we send our

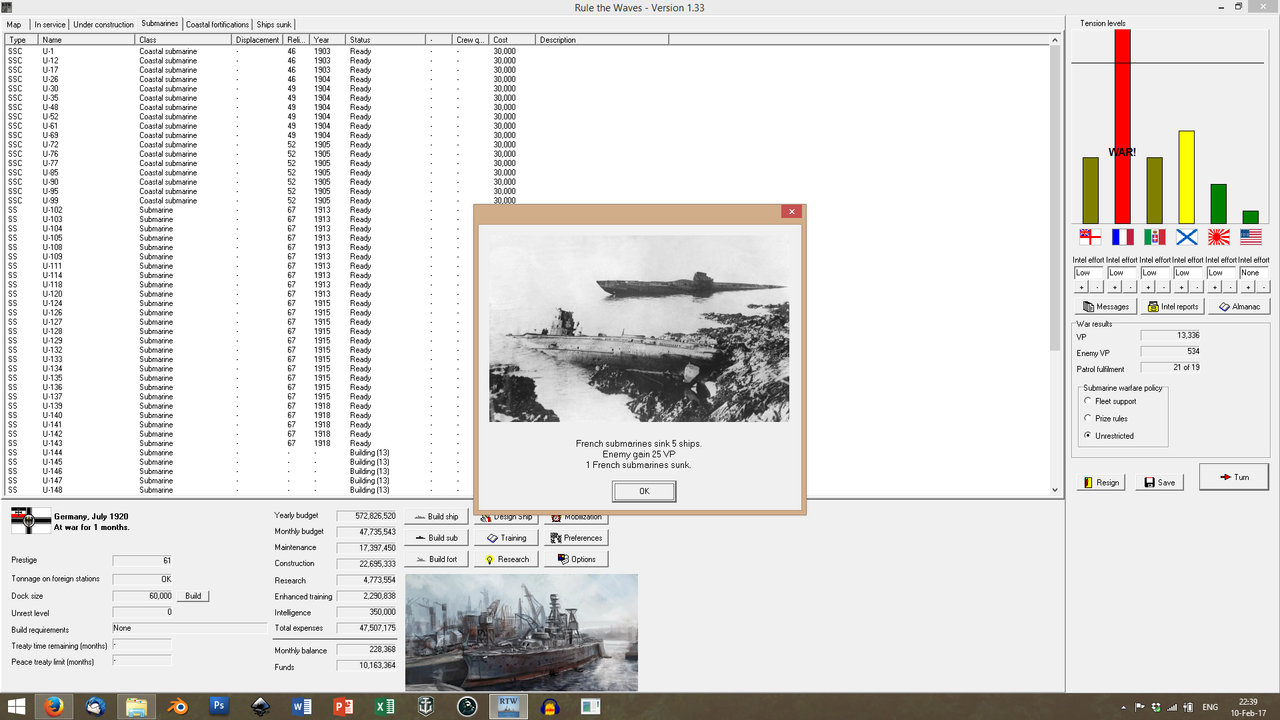

U-Boote out.

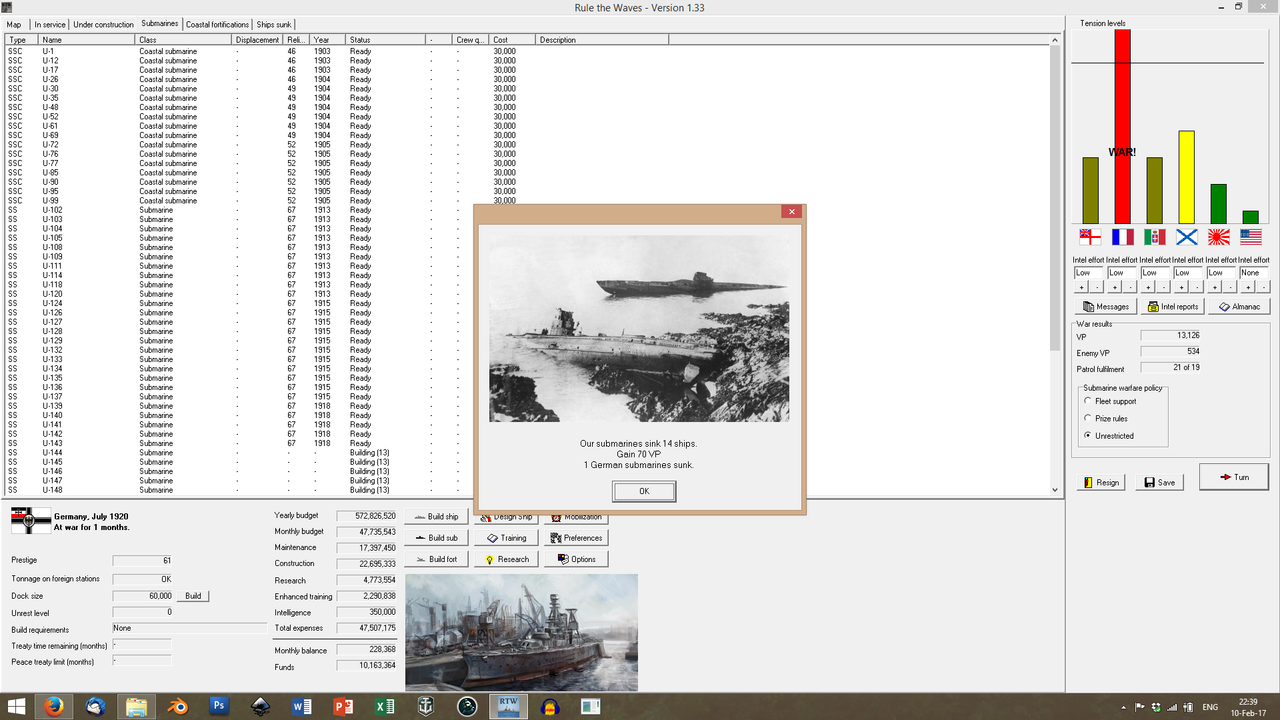

Now, it is interesting to note that the French do not suffer as much as the British here. Nor do they

fail as much in their counter-raiding. They have a modern force, of both submarines and patrol vessels; and their convoys are fewer and better protected than the British ones (not to mention less important to the country's

survival); but they are

inexperienced. The German

Kaleuns, on the other hand, are both highly skilled and utterly

merciless. And the

Pieper crews do not fool around either.

The question is: the French have been humiliated in La Rochelle. Will they push back?

Yes. Yes they will.

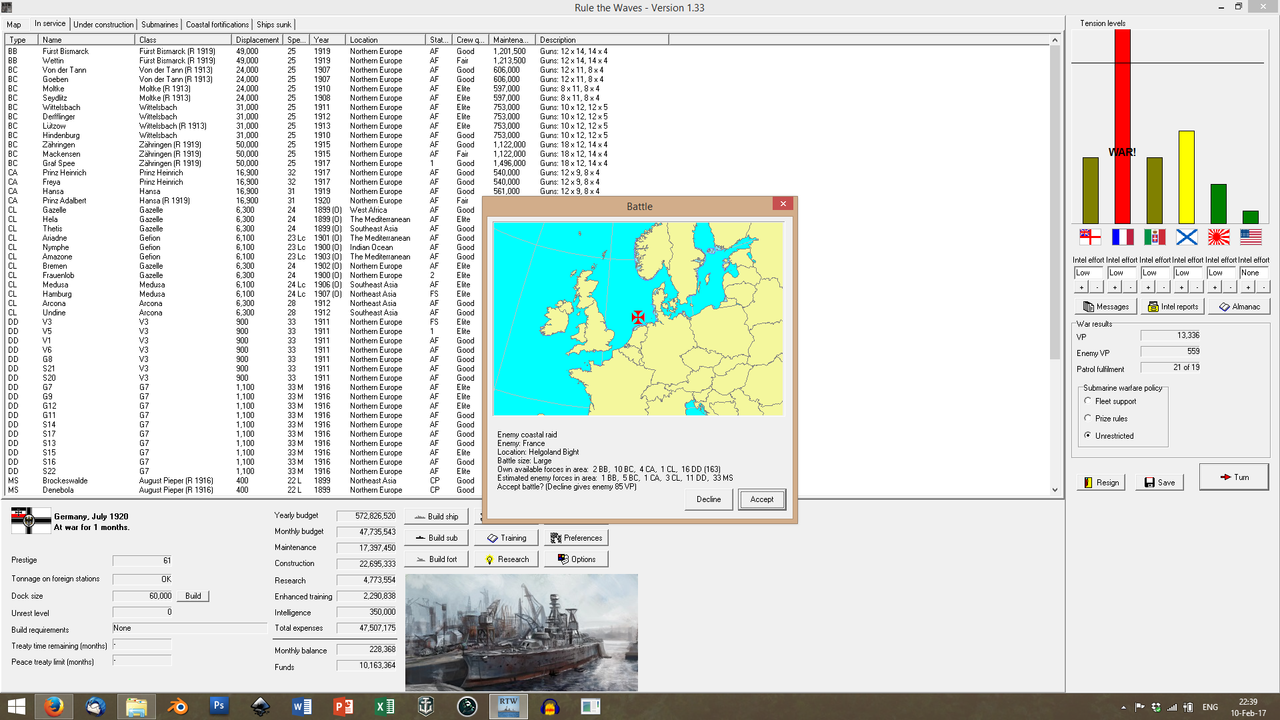

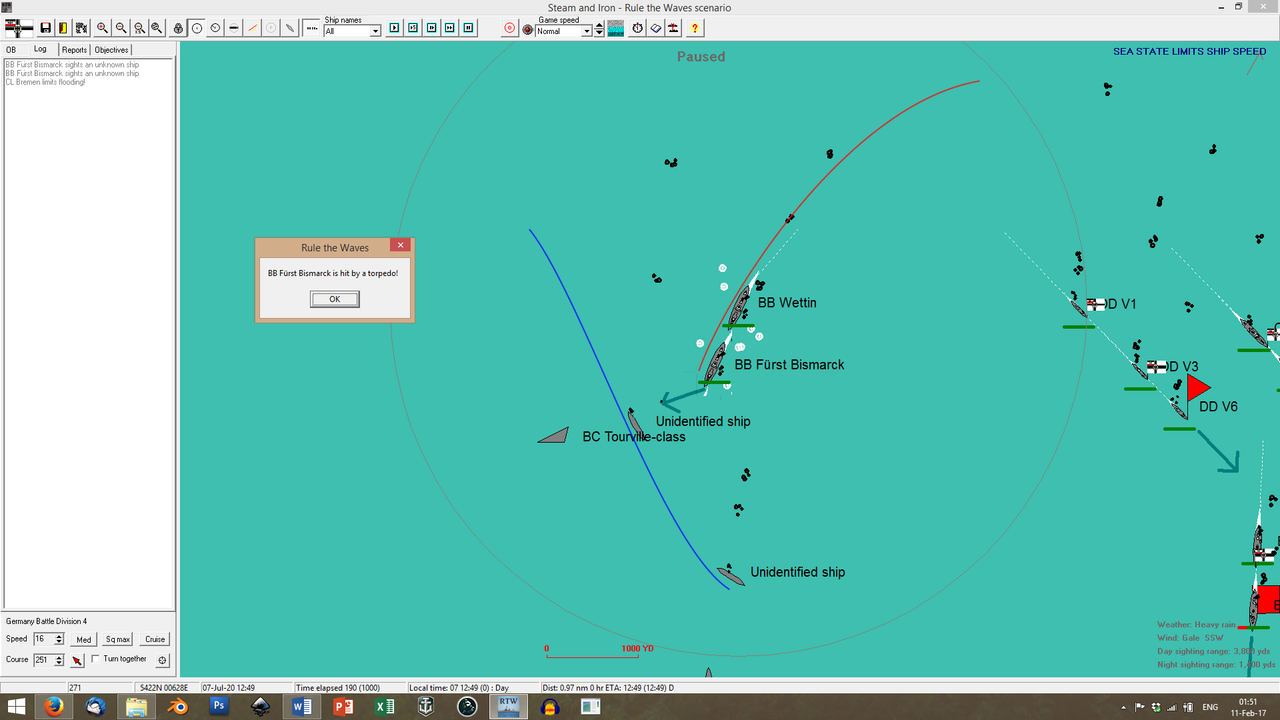

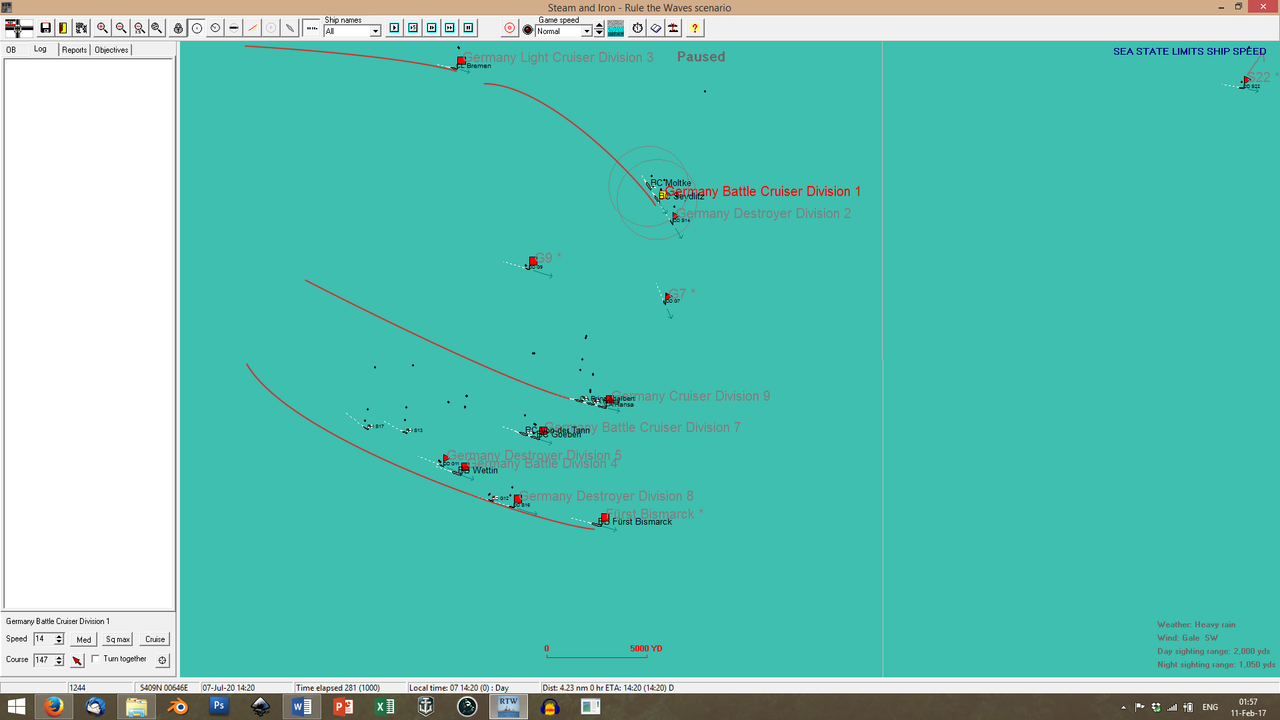

With Hipper's force in drydock, it falls to Scheer to safeguard the home waters. And he does so in his trademark careful fashion, with patrols in force and tireless vigilance.

On the 7th of July, almost a month after the La Rochelle engagement, and with the ground forces preparing for the first large-scale offensive, Scheer is bringing his fleet back from a Long Patrol, trying to reach Helgoland before a summer gale hits. Visibility is minimal; the crews are wet, and tired and miserable.

And, suddenly, there are French ships less than two thousand yards towards the north, closing in fast.

The only appropriate response is 'Da stecken wir ja schön in der Scheisse'.

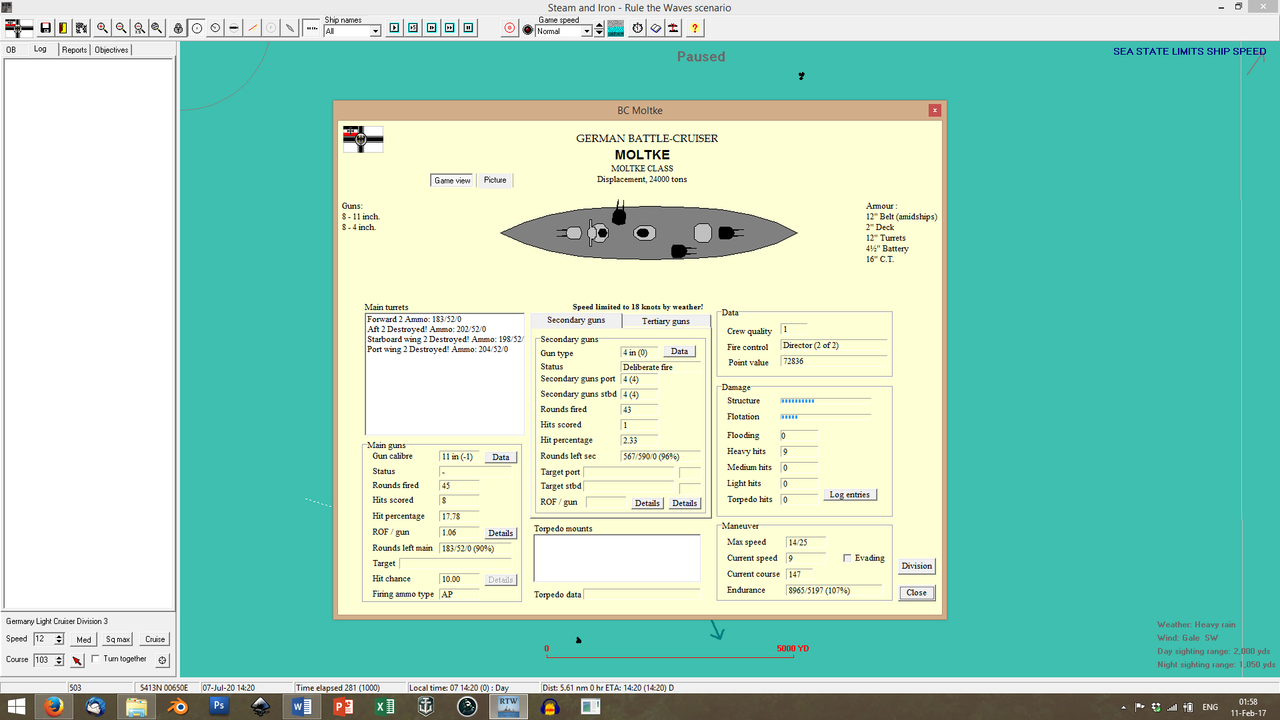

The northernmost German squadron comprises the

Moltke and the

Seydlitz with their

Zerstörer escorts. The old veteran

Schlachtkreuzer are

not ready to engage enemy capitals; thankfully, their

Zerstörers are.

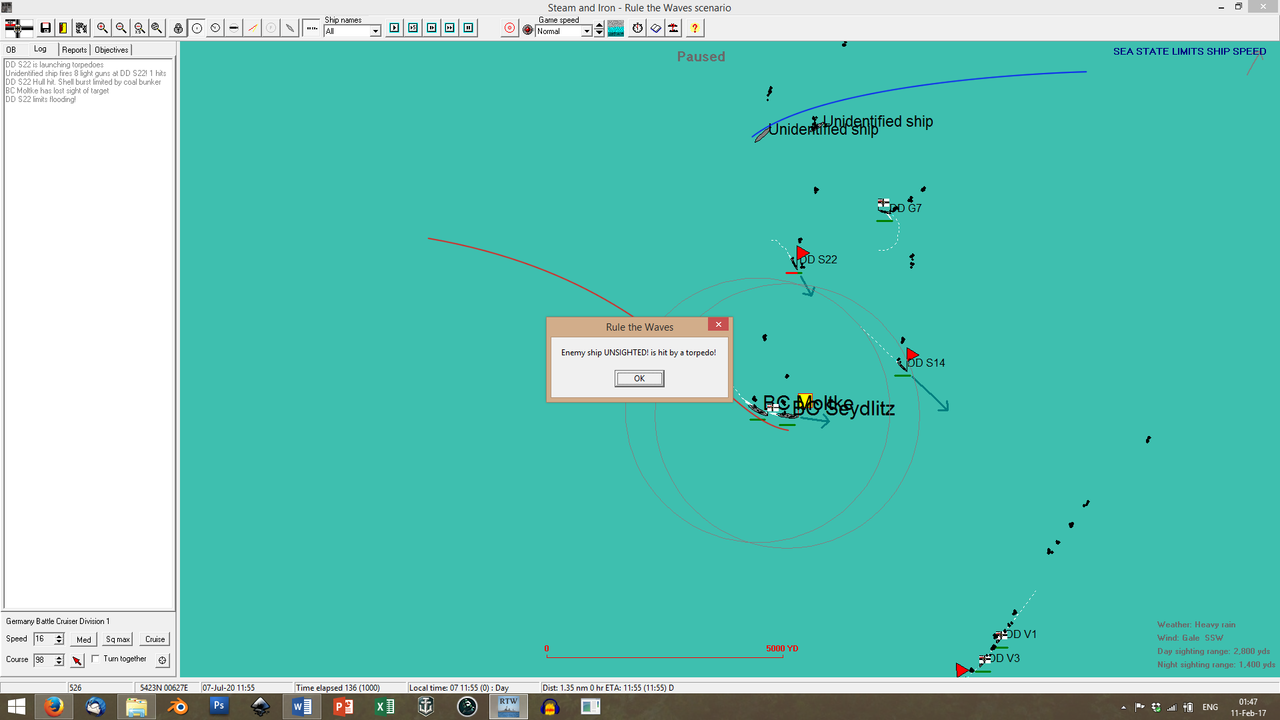

Kapitänleutnant Falke of the

S-22 takes his little tin can on a suicidal run against the enemy ship silhouettes and launches torpedoes from point-blank range. As he turns to escape, his ships is blasted to near-oblivion by heavy-caliber fire; but his torpedo

hits; and it buys enough time for the

Moltke and

Seydlitz to get to battle stations.

Further to the south, Scheer, from the conning tower of the

Bismarck scans the seas with concern. He has heard the gunfire; and the

Bismarck is sounding battle stations, rushing to the north, to assist the old

Schlachtkreuzer. Visibility is

**** and they must not allow themselves to be-

-ENEMY SHIP TO THE NORTH, RANGE 1500 YARDS! RUDDER HARD STARBOARD; ALL GUNS FIRE AT WILL!

The

Bismarck responds to the rudder beautifully. Her wide beam and well-balanced metacentric height make her a very stable gun platform in high seas; and her 14-inchers boom against the silhouetted enemy.

Wettin scores a hit;

Bismarck scores two.

And, twenty seconds later, three more.

Whhooooooooooooomfffff.

Whhooooooooooooomfffff.

The explosion serves as a beacon.

Moltke and

Seydlitz turn, to approach from the north, while

Bismarck and

Wettin turn to meet them. In the south-west, little

Bremen fights against the waves, to reach her capital wards-

-and eats a torpedo for her trouble; a torpedo that blows her newly-repaired bows clean off.

Scheer takes his superdreads around, to investigate the area of the enemy explosion - and hopefully reach

Bremen for assistance. Unfortunately, with the gale messing up signaling, his escorts fall behind. And he pays for it, when his lookouts make out French destroyers in the area, possibly looking to save survivors themselves. He orders an evasive turn to starboard; but it's too late. A torped hits the

Bismarck amidships, on her starboard side.

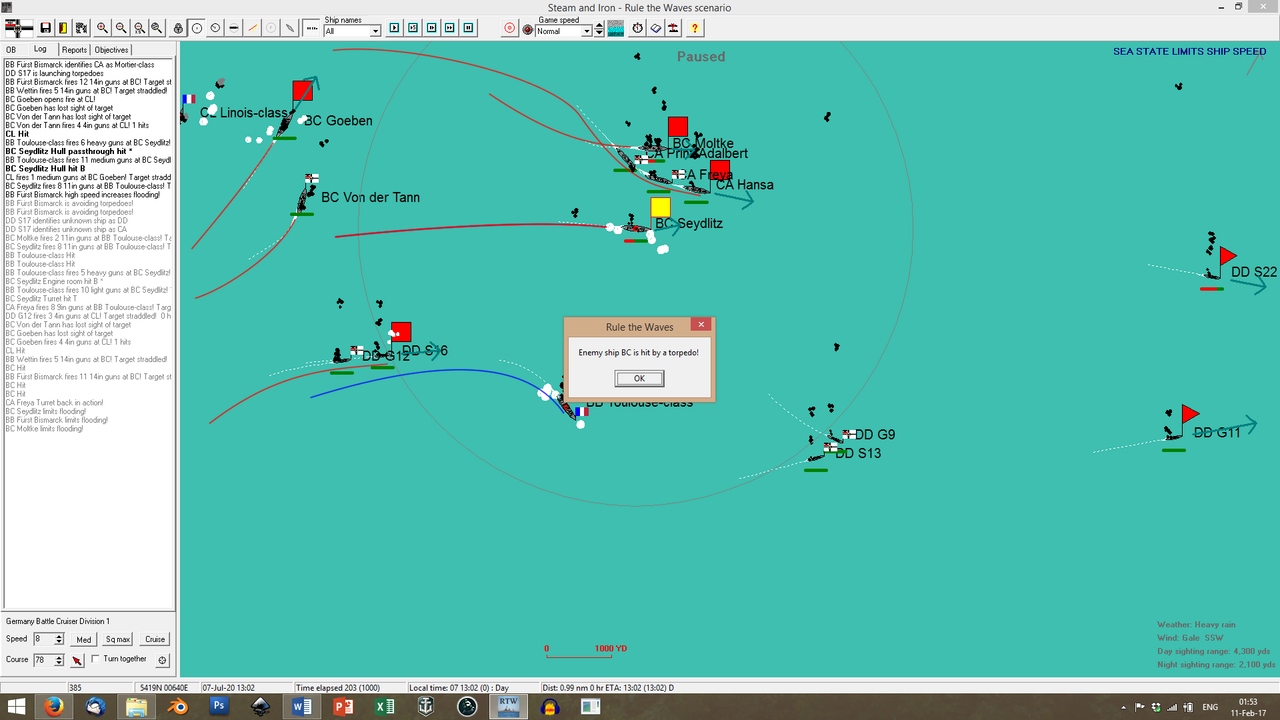

And then - a few terrifying moments of fire and thunder, as what seems to be a bloody French battle-line slices right through the German forces. Some capitals are spotted; and the German

Zerstörer loose their fish in a ragged volley, as they bear and as they

see their opponents. At least one hit is scored-

-but the German forces suffer in return. French guns boom from insight the smoke, fog and rain;

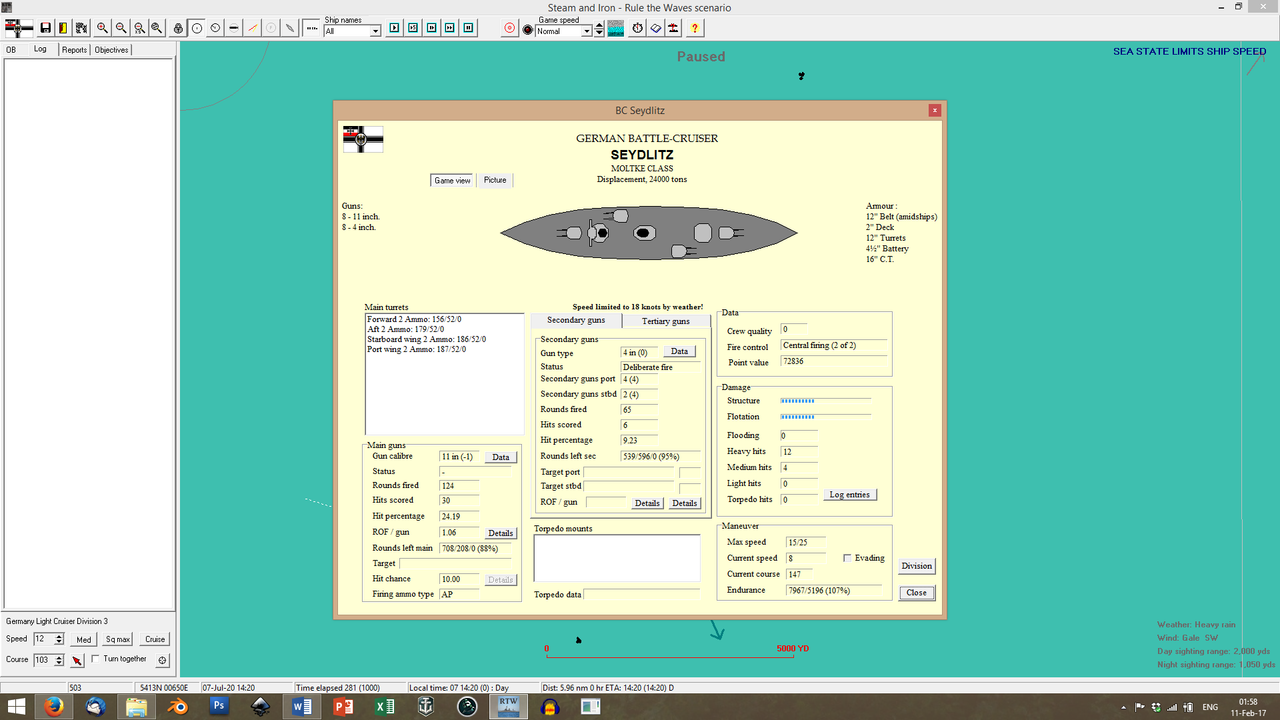

Seydlitz and

Moltke are riddled with holes, both on the superstructure and the waterline.

Moltke loses three of her four turrets, in the most horrifying carnage ever to have been inflicted on a German vessel;

Seydlitz does not fare so badly above the waterline, but several underwater hits rob her of almost half her reserve buyoancy. She loses two of her boilers, is listing heavily and can only do 15 knots.

Nope

Nope. **** that ****. Scheer is

out of there.

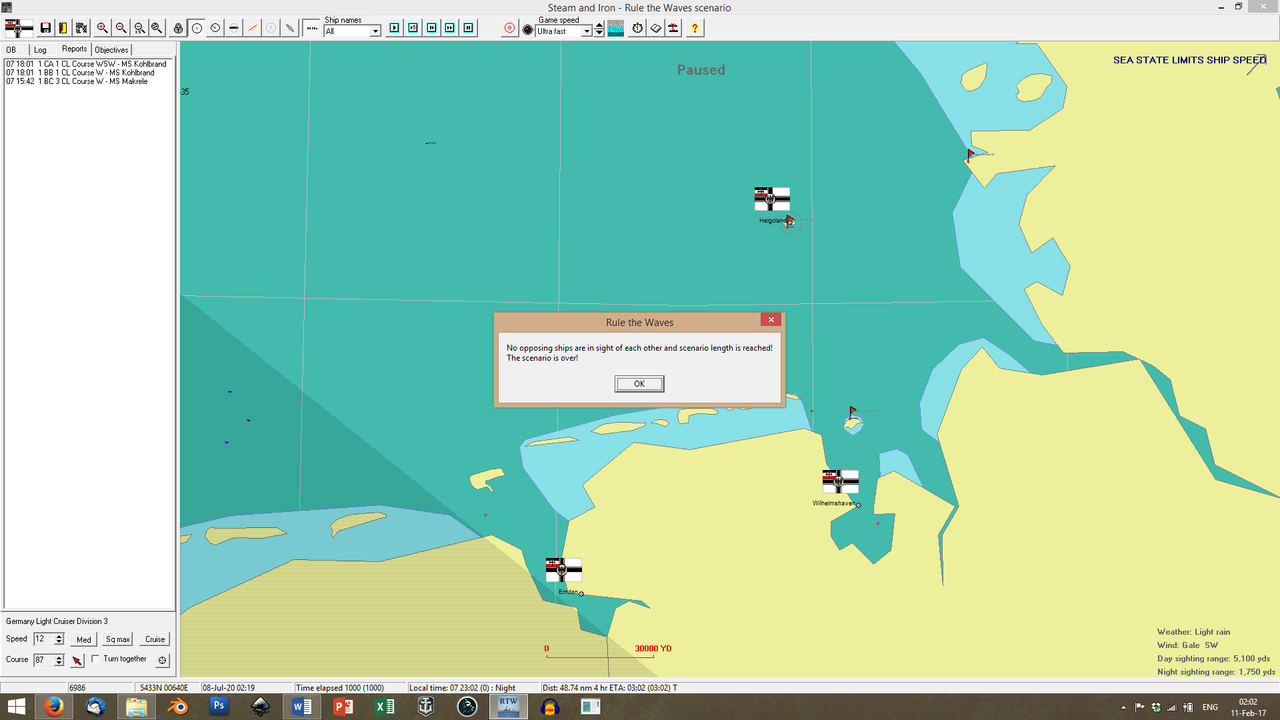

His ships limp into Helgoland four hours later. Morale is low. Scheer can only

imagine what the French are going to be crowing from the-

-WHAT THE ****?

HOW THE

**** DID YOU LOSE THREE BATTLECRUISERS, FRENCHIES?

OK, OK, let's count. One went up like a roman candle; one got torpedoed

once and, OK, the

Bismarcks may have scored a couple of underwater hits on a third one. But

surely that's not enough to

sink a capital ship?

Um Gottes Willen, Baguettes,

what is your ****ing damcon doctrine like?